$\def\d{\mathrm{d}}$It turns out that Yuri's answer to my earlier question, whilst correct (and I thank him for his effort), was not quite what I desired. I had not posed the question properly, so I have chosen to re-ask as I am still struggling to implement the strict inequality constraints.

Let me begin by reposing the question. I wish to extremise $$Q = \int_0^h u \, \, \d y$$ subject to the constraints$$ B = B_0,\ M = M_0,$$ where $$B = \int_0^h ug \, \d y, \ M = \int_0^h \left( u^2 + \int_0^y g(y^*) \, \d y^*\right) \, \d y.$$ An important new difference is that we have that $h$, the upper limit, can vary, and crucially we need

$$u(h) = 0, \ g(h) = 0, \\ \int_0^h u \, \d y> 0, \ \int_0^h g \, \d y = G(h) > 0.$$

Here is my attempt (mostly following @Yuri). We set $$ G(y) = \int_0^y g(y^*) \, \d y^*$$

such that $$B = \int_0^h uG' \, \d y, \ M = \int_0^h u^2 + G \, \d y$$ and hence the Lagrangian becomes

$$L(u,G,G',\lambda,\mu) = Q + \lambda(B-B_0) + \mu(M-M_0).$$ The variations of this (using Euler-Lagrange $\frac{\partial L}{\partial F} - \frac{\d}{\d y}\frac{\partial L}{\partial F'} = 0$) become

$$1 + \lambda G' + 2\mu u = 0, \ \mu - \lambda u' = 0, \\ \int_0^h uG' = B_0, \ \int_0^h u^2 + G = M_0.$$

The second equation here tells us

$$u' = \frac{\lambda}{\mu} \Longrightarrow u = \frac{\lambda}{\mu}y + u_0.$$

Now since $h$ can vary we have two further transversality conditions

$$\left.\frac{\partial L}{\partial G'}\right|_{y=h} = 0, \ \left.L - G' \frac{\partial L}{\partial G'}\right|_{y=h} = 0.$$

The first transversality condition tells us that

$$\lambda u(h) = 0 \Longrightarrow u(h) = -\frac{\lambda}{\mu} \Longrightarrow u = -\frac{\mu}{\lambda}\left(h-y\right).$$

This is great as it satisifes $u(h) = 0$.

The second transversality condition tells us (using the first variation equation to give us $G$) that

$$\mu G(h) = 0 \Longrightarrow h = \frac{\lambda}{\mu^2}.$$

(However I think this condition violates the requirement $G(h) > 0$)

We can now calculate everything we need,

$$B_0 = -\frac{1}{6\mu^3}, \ M_0 = \frac{\lambda}{2\mu^4} \\ \lambda = \frac{M_0}{3\left(6^{1/3}B_0^{4/3}\right)}, \ \mu = -\frac{1}{6^{1/3}B_0^{1/3}}, \ h = \frac{2^{1/3}M_0}{3^{2/3}B_0^{2/3}} \\ Q = \frac{M_0}{6^{1/3}B_0^{1/3}}.$$

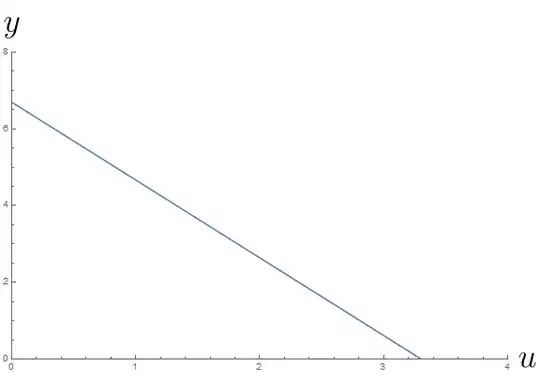

If we now sub in some values $B_0 = 6, M_0 = 36.5$ I am especially happy with the answer for $Q \approx 11.05, h \approx 6.696$ as it verifies a separate result I have reached. The problem comes with the profile for $g$. If look at the profile for $u$ we have everything behaving as expected. $u(h) = 0$ and $\int_0^h u \, \, dy >0$.

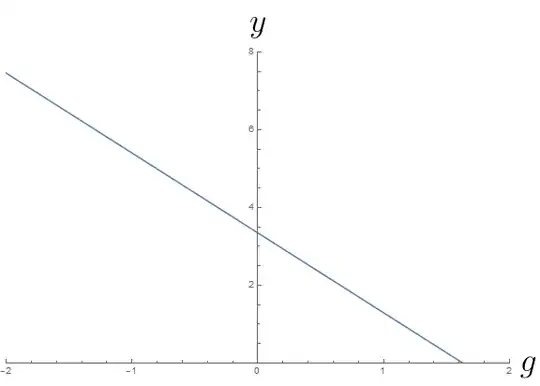

However, the issue comes when looking at the profile for $g$. We can immediately see that $g(h) \neq 0$ (strangely $g(h/2) = 0$), and also we have $\int_0^h g \, \d y = 0$ which is not strictly bigger than 0.

So my question is, how can I build the machinery for the constraints on $g$ into the Lagrangian. I have read a little online about possibly using slack variables, but I am not sure how to implement them. Any pointers would be greatly appreciated.

Interestingly, if I were to transform the profile of $g$ to $\hat{g}$ such that $g(h/2) = \hat{g}(h) = 0$ and $g(0) = g^*, \hat{g}(0) = g^* / 2$ the solution for $\hat{g}$ would match the separate result I have reached identically.

EDIT

So I have a found a paper in which the author uses slack variables to impose a condition $\theta_z \geq 0$, my thinking is that this condition is equivalent to $G' >0$. Though in his derivation, his multiplier becomes a function of $z$. Something that I have never seen before.

EDIT 2

I am now not convinced the second transversality condition is correct. This condition $G(h) = \int_0^h g = 0$ is what is forcing the profile to be negative above $h/2$ (to keep the area 0). This actually contradicts the essential requirement that $\int_0^h g > 0$.

EDIT 3

I thought it would be helpful to add some further motivation. This method of calculus of variations as described above finds two solution profiles for $u$ and $g$ that are given by $$ u_1 = \frac{3 B_0 (h - y)}{M_0} \\ g_1 = \frac{3 \left(6 B_0^2 (h-y)-6^{1/3} B_0^{4/3} M_0\right)}{M_0^2} $$

which we can see satisfy the equations and maximise $Q$.

I believe that the true solution I am seeking is given by profiles

$$ u_2 = \frac{3 B_0 (h - y)}{M_0}, \ g_2 = \frac{9 B_0^2 (h-y)}{2 M_0^2}, \ h = \frac{2^{1/3}M_0}{3^{2/3}B_0^{2/3}}.$$

which can be shown to satisfy all the equations for $M,B$ and also give the same maximal $Q$. Furthermore, the profile for $g_2$ in particular satisfies the requirements that $g_2(h) = 0$ and $\int_0^h g_2 > 0$.

It would appear to me that the $g_1, g_2$ profiles are equivalent solutions and I would expect that the calculus of variations to find both? I find it confusing that it doesn't.

I suppose one could frame the question in the way. What constraints needed to be added to the Lagrangian such that the calculus of variations gives the me the desired $g_2$ profile, rather than the unphysical $g_1$ profile?

We need $g(0) > 0, u(0) > 0$ and $g(h) = 0, u(h) = 0$.

– mch56 Apr 28 '17 at 11:57As we have $\int_0^h u' ,,dy = u(h) - u(0)$. We need $u(h) = 0$ that is true, but $u(0) > 0$ so $\int_0^h u' ,,dy \neq 0$. Similarly we need $g(h) =0$ but $g(0) > 0$, so $\int_0^h G'' ,,dy \neq 0$

– mch56 Apr 28 '17 at 13:05