As noted in the comments, $f^*$ and $g^*$ are not necessarily functions after rotation. For example, consider the upper semicircle $y = \sqrt{1-x^2}$; any amount of rotation will cause it to no longer be a function.$\newcommand{\degs}{^\circ}

\newcommand{\cut}{\, \backslash \,}

\newcommand{\AND}{\ {\rm{\small{AND}}}\ }

\newcommand{\OR}{{\ \rm{\small{OR}}}\ }

\newcommand{\NOT}{\ {\rm{\small{NOT}}}\ }

\newcommand{\Implies}{\Rightarrow}

\newcommand{\If}{\Leftarrow}

\newcommand{\Iff}{\Leftrightarrow}

\newcommand{\x}{\times}

\newcommand{\R}{\mathbb{R}} \newcommand{\C}{\mathbb{C}} \newcommand{\N}{\mathbb{N}} \newcommand{\Z}{\mathbb{Z}} \newcommand{\Q}{\mathbb{Q}}

\newcommand{\E}{\operatorname{\rm{\small{E}}}}

\renewcommand{\Re}{\operatorname{Re}} \renewcommand{\Im}{\operatorname{Im}}

\newcommand{\dash}{\textrm{-}}

\newcommand{\der}{\partial}

\newcommand{\del}{\nabla}

\newcommand{\inv}{{\sim}}

\newcommand{\eps}{\varepsilon}

\newcommand{\dedent}{\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!\!}$

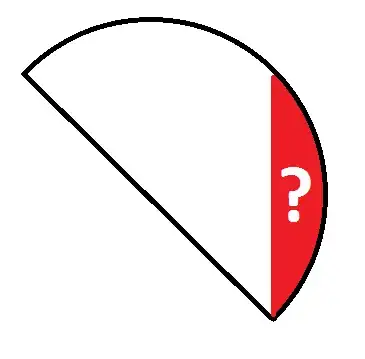

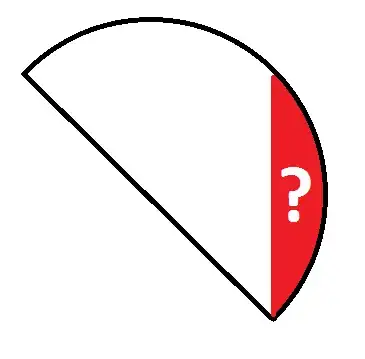

However, we really do need the rotated curves to be functions if we want a notion of "above" and "below" to make sense. To see what I mean, let $f$ denote the upper unit semicircle I defined earlier, and let $g$ be identically zero on $[-1,\ 1]$. If we rotate them both clockwise we get the following:

In the red zone, the rotated $f^*$ has no $g^*$ underneath, leaving the comparison undefined.

So we need to ensure that $f^*$ and $g^*$ are well-defined functions. To do so, we need to impose some special conditions onto both $f$ and $g$. I don't know what the bare minimum necessary conditions are, but I do have a reasonably broad set of sufficient conditions that work. I will state them as part of the following proposition which, I think, is the essential gist of what you're wanting to prove:

Proposition: Let $\Delta\theta$ be an angle in the open interval $(0,\ \pi/2)$, and let $f$ and $g$ be differentiable functions on the closed interval $[a,b]$ such that the following hold:

- $f(a) = g(a) \AND f(b) = g(b)$,

- $f(x) \geq g(x)$ for all $x \in [a,b]$,

- $f'(x),\ g'(x) < \cot \Delta\theta$ for all $x \in [a,b]$.

Then the counterclockwise rotations $f^*$ and $g^*$ by $\Delta\theta$ exist on the shifted interval $[a^*, b^*]$ (to be computed later) and satisfy $f^*(x) \geq g^*(x)$ on it.

For ease of presentation, this proposition is restricted to counterclockwise rotations, but the more general version for clockwise rotations is stated similarly to this one.

The key condition I imposed is that the derivatives of both $f$ and $g$ must be bounded by the cotangent of the rotation angle. To see the intuitive reason I did this, I pictured the rotation being a rotation of the axes instead of the curves. In that case, the question of whether the rotated curves will satisfy the vertical line test becomes equivalent to asking whether any line of the form

$$ y = (\cot \Delta\theta) x + b $$

intersects any one unrotated curve twice.

With that I'll dive into the proof of the Proposition.

(Note: every step may not be perfectly rigorous, but I think it works pretty well, and it's probably briefer than a thorough proof.)

The first thing we need to show is that $f^*$ and $g^*$ are well-defined functions. To do that, let's suppose that they're not. In that case the rotations fail the vertical line test, or equivalently, there exists a line

$$ y = (\cot \Delta\theta)x + b $$

that intersects either $f$ or $g$ twice. Assume without loss of generality that $f$ is guilty of this (the logic is the same for $g$). Let's call the two $x$-values of the two intersection points $\alpha$ and $\beta$. In that case the two points $\big(\alpha,\ f(\alpha) \big)$ and $\big(\beta,\ f(\beta) \big)$ must lie on a line with slope $\cot \Delta\theta$. Therefore

$$ \frac{f(\beta) - f(\alpha)}{\beta - \alpha} = \cot \Delta\theta $$

Then by the Mean Value Theorem, there must exist some $c$ between $\alpha$ and $\beta$ such that $f'(c) = \cot \Delta\theta$. This contradicts our assumption that $f'(x) < \cot \Delta\theta$ for all $x \in [a,b]$. $\checkmark$

Now we prove that the rotations still preserve the order. Consider any $x^* \in [a^*, b^*]$. We want to show $f^*(x^*) \geq g^*(x^*)$. Now the points $\big(x^*, f^*(x^*) \big)$ and $\big(x^*, g^*(x^*) \big)$ correspond to two points $\big(x_f, f(x_f) \big)$ and $\big(x_g, g(x_g) \big)$ in unrotated space. The statement $f^*(x) \geq g^*(x)$ is equivalent to saying that $x_f \geq x_g$

i.e. $f^*(x^*)$ is above $g^*(x^*)$ if and only if the corresponding point $\big(x_f, f(x_f) \big)$ is upslope from $\big(x_g, g(x_g) \big)$.

To prove it, suppose not. Suppose $x_f < x_g$. Then the two points $\big(x_f, f(x_f) \big)$ and $\big(x_g, g(x_g) \big)$ lie on a line of slope $\cot \Delta\theta$ and so

$$ \frac{g(x_g) - f(x_f)}{x_g - x_f} = \cot \Delta\theta $$

Now we assumed that $f(x) \geq g(x)$ for any $x$, so that means $f(x_g) \geq g(x_g)$. Hence

$$ \frac{f(x_g) - f(x_f)}{x_g - x_f} \geq \frac{g(x_g) - f(x_f)}{x_g - x_f} = \cot \Delta\theta $$

So by the Mean Value Theorem we again have a $c$ between $x_f$ and $x_g$ such that $f'(c) \geq \cot \Delta\theta$. A contradiction. $\checkmark$

And lastly a note on how to compute $a^*$ and $b^*$. We can treat a point $(x,y)$ on the plane as the complex number $x+yi$. If we want to rotate that point about the origin by $\Delta\theta$ radians (either positive or negative), we simply multiply:

$$ x^* + y^*i = (x+yi)e^{\theta i} $$

which yields

$$ x^* + y^*i = x \cos \Delta\theta - y \sin \Delta\theta + (y \cos \Delta\theta + x \sin \Delta\theta)i $$

Substituting

\begin{align}

x &= a,\ b \\

y &= f(a),\ f(b)

\end{align}

respectively and taking the real part will give $a^*$ and $b^*$.

For your particular $f$ and $g$:

\begin{align}

f(x) &= \sqrt{1-x^2} \\

g(x) &= 1-x

\end{align}

on the interval $[0,1]$ I get $a^*$ and $b^*$:

\begin{align}

a^* &= \Re \left(i \cdot e^{\pi/4 i} \right) = \Re \left(e^{3\pi/4 i} \right) = \cos(3\pi/4) = -\sqrt{2}/2 \\

b^* &= \Re \left(1 \cdot e^{\pi/4 i} \right) = \cos(\pi/4) = \sqrt{2}/2

\end{align}

yielding an interval length of $\sqrt{2}$ which is expected since that is the length of the diagonal of $y = 1-x$ on $[0,1]$.