$\newcommand{\bbx}[1]{\,\bbox[15px,border:1px groove navy]{\displaystyle{#1}}\,}

\newcommand{\braces}[1]{\left\lbrace\,{#1}\,\right\rbrace}

\newcommand{\bracks}[1]{\left\lbrack\,{#1}\,\right\rbrack}

\newcommand{\dd}{\mathrm{d}}

\newcommand{\ds}[1]{\displaystyle{#1}}

\newcommand{\expo}[1]{\,\mathrm{e}^{#1}\,}

\newcommand{\ic}{\mathrm{i}}

\newcommand{\mc}[1]{\mathcal{#1}}

\newcommand{\mrm}[1]{\mathrm{#1}}

\newcommand{\pars}[1]{\left(\,{#1}\,\right)}

\newcommand{\partiald}[3][]{\frac{\partial^{#1} #2}{\partial #3^{#1}}}

\newcommand{\root}[2][]{\,\sqrt[#1]{\,{#2}\,}\,}

\newcommand{\totald}[3][]{\frac{\mathrm{d}^{#1} #2}{\mathrm{d} #3^{#1}}}

\newcommand{\verts}[1]{\left\vert\,{#1}\,\right\vert}$

With $\ds{\sigma > 0}$, the answer is given by the following expression:

\begin{align}

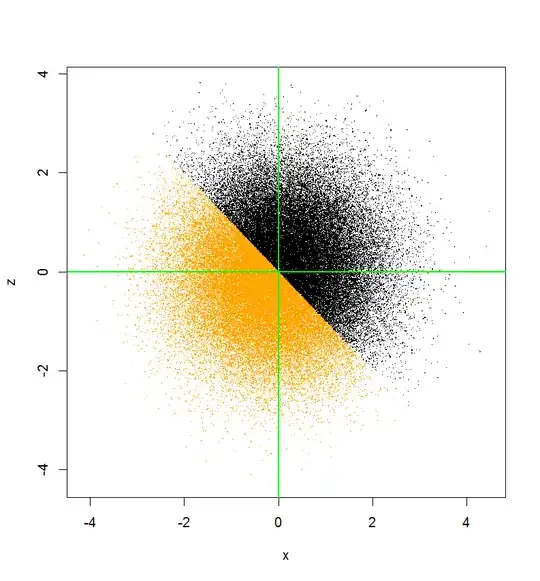

&\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}

\bracks{{1 \over \root{2\pi}\sigma}\,

\exp\pars{-\,{x^{2} \over 2\sigma^{2}}}}

\bracks{{1 \over \root{2\pi}\sigma}\,

\exp\pars{-\,{z^{2} \over 2\sigma^{2}}}}\bracks{x + z < 0}\bracks{z > 0}

\dd x\,\dd z

\\[5mm] = &\

{1 \over 2\pi\sigma^{2}}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}

\exp\pars{-\,{{x^{2} + z^{2} \over 2\sigma^{2}}}}

\bracks{0 < z < -x}\dd x\,\dd z

\\[5mm] = &\

{1 \over \pi}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}\int_{-\infty}^{\infty}

\expo{-x^{2}\ -\ z^{2}}\,\,\bracks{0 < \root{2}\sigma z < -\root{2}\sigma x}

\dd x\,\dd z

\\[5mm] = &\

{1 \over \pi}\int_{0}^{2\pi}\int_{0}^{\infty}

\expo{-r^{2}}\,\,\bracks{0 < r\sin\pars{\theta} < -r\cos\pars{\theta}}r

\,\dd r\,\dd\theta

\\[5mm] = &\

{1 \over \pi}\int_{0}^{2\pi}\bracks{0 < \sin\pars{\theta} < -\cos\pars{\theta}}\

\underbrace{\int_{0}^{\infty}\expo{-r^{2}}r\,\dd r}_{\ds{1 \over 2}}\

\dd\theta =

{1 \over 2\pi}\int_{0}^{\pi}

\bracks{\sin\pars{\theta} < -\cos\pars{\theta}}\,\dd\theta

\\[5mm] = &\

{1 \over 2\pi}\int_{3\pi/4}^{\pi}\,\dd\theta =\

\bbox[#ffe,5px,border:1px dotted navy]{\ds{1 \over 8}}

\end{align}