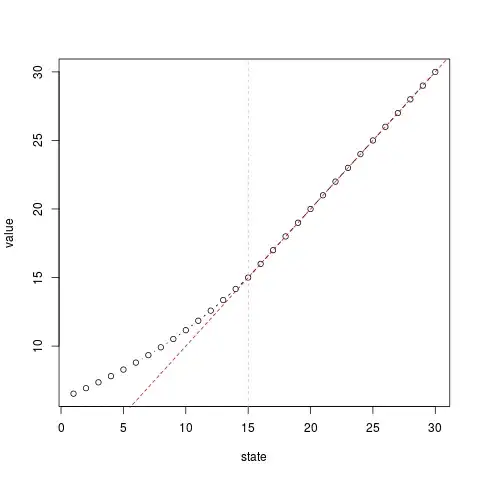

It's not hard to see that the optimal strategy in this game is "stop on $k$ or higher," for some positive integer $k$. This is because what is optimal is only determined by your current score, not your history of rolls, and if rolling again on $k$ is unwise, then rolling again on $k+1$ is unwise as well (you stand to gain the same amount from future rolls, but have more to lose).

Let's compare the strategies "stop on $k$ or higher" with "stop on $k+1$ or higher". If your score is never $k$, then these strategies result in the same final score. If you do reach $k$, then the first strategy will result in $k$, while the second will result in $\frac56k+\frac16(1+2+3+4+5)$. Comparing these, we see that the stop on $k$ strategy is better precisely when $k>15$, is worse when $k<15$, and you should be indifferent between then two when $k=15$.

Here is a proof which is more obviously rigorous. Let $V(k)$ denote the expected gain from future rolls when you play the optimal strategy, starting from a total of $k$. By considering the two options of roll again or stop, we get

$$

V(k)=\max\left(0,\frac16\left(\sum_{i=1}^5 (V(k+i)+i)\right)+\frac16(-k)\right)

\\=\max\left(0,\frac{15-k}6+\frac16\sum_{i=1}^5V(k+i)\right)

$$

We can now prove that $V(k)>0$ if and only if $k<15$. This means that is strictly optimal to roll again if and only if your total score is less than $15$.

Certainly, if $k<15$, then $V(k)\ge \frac{15-k}6+\frac16\sum_{i=1}^5V(k+i)\ge \frac{15-k}6$, because $V(k+i)\ge 0$. We conclude that $V(k)>0$ when $k<15$, as claimed. However, when $k\ge 15$, more care is required.

First of all, I can prove that

$$

V(k)\le 15\text{ for all }k.\tag{$*$}

$$

To see this, consider a modified game where rolling a six simply stops the game, without taking away your accumulated points. Certainly, this game is more favorable to the player. For the modified game, it is optimal to roll until you get a six, so the expected gain from future rolls is exactly $5\cdot 3$, as you will roll on average $1/(1/6)=6$ times more, and the first five rolls give you three points each on average.

Using $(*)$, you can prove that $V(k)=0$ for all $k\ge 90$, because

$$

\frac{15-k}6+\frac16\sum_{i=1}^5V(k+i)

\le \frac{15-k}6+\frac16\sum_{i=1}^515

=\frac{90-k}6

\le 0.

$$

We can now prove that $V(k)=0$ for the remaining cases $15\le k\le 89$ by reverse induction on $k$. That is, given $k\ge 15$, we assume that $V(\ell)=0$ for all $\ell>k$, and use this to prove $V(k)=0.$ The proof is simple:

$$

V(k)

=\max\left(0,\frac{15-k}6+\frac16\sum_{i=1}^5V(k+i)\right)

=\max\left(0,\frac{15-k}6+0\right)=0.

$$

@lulu: Thank you for the hint!

Trying to follow:

$0 = (N+3)\frac{5}{6} - N\frac{1}{6}$, which doesn't help a lot as N = -15/4...

– Kulawy Krul Oct 20 '16 at 12:40