There are many alternatives, and you didn't give us enough information to choose between them intelligently. So, here are a few options; you can choose.

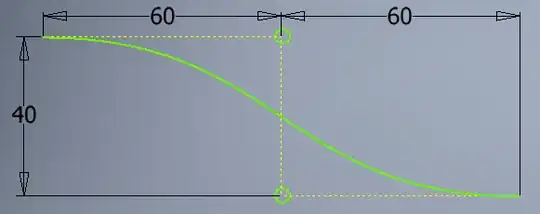

I assume that the coordinate system origin is at the center of the curve.

(1) Parametric Cubic in Bézier Form

This is the obvious choice because the symbols on your picture look like the control points of a cubic Bézier curve. These control points are $\mathbf{P}_0 = (-60,20)$, $\mathbf{P}_1 = (0,20)$, $\mathbf{P}_2 = (0,-20)$, and $\mathbf{P}_3 = (60,-20)$. Then the curve is

$$

\mathbf{P}(t) = (1-t)^3 \mathbf{P}_0 + 3t(1-t)^2 \mathbf{P}_1 +

3t^2(1-t) \mathbf{P}_2 + t^3 \mathbf{P}_3

$$

In fact, more generally, you can take $\mathbf{P}_1 = (-k,20)$, $\mathbf{P}_2 = (k,-20)$, and you'll still get a curve of roughly the desired shape. You can adjust $k$ to get exactly the shape you want.

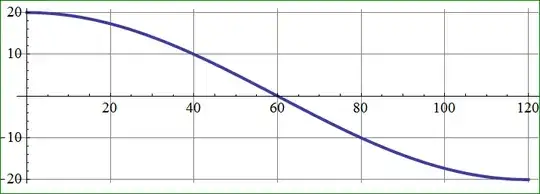

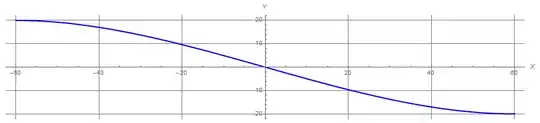

(2) Real-Valued Cubic in Algebraic Form

If you're going to use the curve as a "law" to control variation of some variable, then you want it to be in the form of a real-valued function $y=f(x)$. The parametric equation given above is inconvenient because, given a value of $x$, it's not easy to find the corresponding value of $y$. A suitable equation is:

$$

y = px(x^2 - q)

$$

Using the relations $y(60) = -20$ and $y'(60)=0$, you can calculate $p$ and $q$.

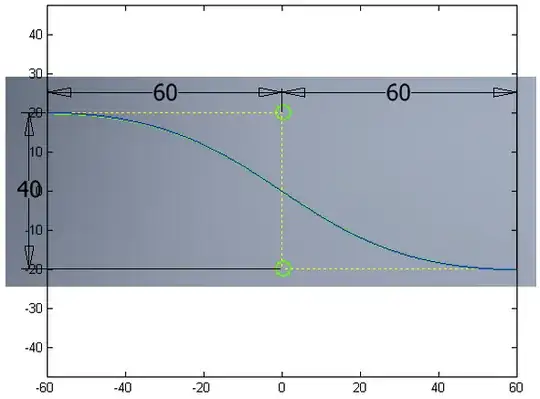

(3) Real-Valued Cubic in Bézier Form

Another option is to write the equation in Bézier form, again. If we let $u = \tfrac{1}{120}(x+60)$, then $u= 0$ when $x=-60$ and $u=1$ when $x=60$. The equation of the curve is

$$

y = a(1-u)^3 + 3au(1-u)^2 - 3au^2(1-u) - au^3

$$

where $a=20$. In a CAD system, you can construct this curve by using the control points $\mathbf{P}_0 = (-60,20)$, $\mathbf{P}_1 = (-20,20)$, $\mathbf{P}_2 = (20,-20)$, and $\mathbf{P}_3 = (60,-20)$. So, this is the case $k=20$ of #1 above.

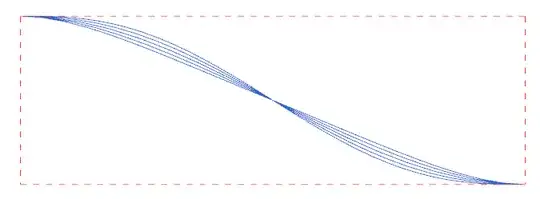

(4) Real-Valued Quintic in Bézier Form

One problem with the real-valued cubics is that they give you no freedom to adjust the shape of the curve. To get some adjustment freedom, you can use a quintic curve, instead. Again, it's easiest to write this in Bézier form. So, as before, we let $u = \tfrac{1}{120}(x+60)$. Then the equation of a suitable quintic is

$$

y = a(1-u)^5 + 5au(1-u)^4 + 10bu^2(1-u)^3 - 10bu^3(1-u)^2 - 5au^4(1-u) - au^5

$$

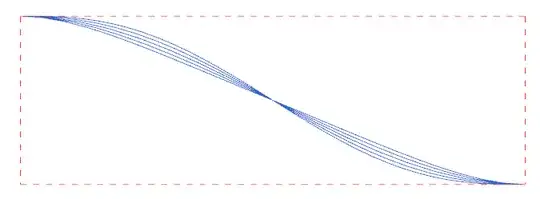

where $a=20$, again. You can change the value of $b$ to adjust the shape of the curve. In your CAD system, you can construct this curve using the control points $\mathbf{P}_0 = (-60,20)$, $\mathbf{P}_1 = (-36,20)$, $\mathbf{P}_2 = (-12,b)$, $\mathbf{P}_3 = (12,-b)$, $\mathbf{P}_4 = (36,-20)$, and $\mathbf{P}_5 = (60,-20)$. The particular choice $b=20$ gives you a curve whose second derivatives are zero at the start and end, which may have some merit in your application. Here are curves with $b = 0,5,10,15,20$.

(5) Quadratic B-spline

Using four control points (like the ones described in #1 or #3), you can define a b-spline curve of degree 2 (i.e. quadratic) that has two segments. Each quadratic segment will actually be a parabola, so the solution is then two parabolas joined end-to-end with tangent continuity. There will be a discontinuity of curvature at the inflexion point where the two pieces meet, and this might be a problem in an aerodynamics application. None of the other solutions I listed have this problem.

(6) Trigonometric Solutions

Several people gave solutions using trigonometric functions. I don't recommend these. CAD systems usually support only polynomial and rational curves (Bézier curves and NURBS curves). They don't support curves described by trigonometric functions. So, if you use trig functions, you will have to approximate, and you'll end up with a spline curve with many segments and wiggly curvature, which will be bad for aerodynamics. All the curves I suggested above can be exactly represented in a typical CAD system, so they don't have this problem.

1+xx(2x-3)– Martijn Courteaux Apr 20 '16 at 09:16