When I see answers regarding proofs such as the one mentioned here, it seems that there is a considerable diversity of ways to attempt to look at this proof. Similarly, although this sum of squares question is very different, I was wondering if there was a geometric interpretation to the following problem:

Prove that given $ a,b,c,d \in \mathbb{Z} \ \ \Rightarrow \ \ \exists \ u,v, \in \mathbb{Z} \ \ s.t. $ $$ (a^{2} + b^{2})(c^{2} + d^{2}) = u^{2} + v^{2} $$

I have mentioned my solution to the problem using basic tools from my complex analysis class.

We write the statement as the product of complex conjugates to prove this theorem:

$ a^{2} + b^{2} = a^{2} - b^{2} (-1) = a^{2} - b^{2} i^{2} $

$ = a^{2} - (bi)^{2} = a^{2} - (ab) i + (ab) i - (bi)^{2} $

$ = a(a-bi) + bi (a-bi) $

$ = (a+bi)(a-bi) $

Similarly, we repeat the procedure for $c^{2} + d^{2}$ to get the expression:

$ (c+di)(c-di) $

Taking the product:

$ = [(a+ bi)(a- bi)] [(c+di)(c-di)]$

$ = [(a+bi)(c+di)][(a-bi)(c-di)] $

The numbers in both terms are complex conjugates

So, we can express them in terms of $u$ and $v$.

This gives us: $ (u+vi)(u-vi) $

$ \therefore u + vi = (a +bi)(c+di)$

$ \therefore a(c+di) + bi(c+di) $

$ \therefore (ac) + (ad)i + (bc)i + (bd)(i^{2}) $

$ \therefore (ac) + (ad)i + (bc)i + (bd)(-1) $

$ \therefore (ac - bd) + (ad + bc)i \equiv u + vi $

We we are left with expressions to determine u and v for all integers a,b,c,d.

$ u = ac - bd $

$ v = ad + bc $

These satisfy our original statement. For example:

$ (2^{2} + 3^{2})(4^{2} + 5^{2}) = (4+9)(16+25) = 533 $

$ u = (2)(4) - (3)(5) = 8 - 15 = -7 $

$ v = (2)(5) + (3)(4) = 10 + 12 = 22 $

$ u^{2} + v^{2} = (-7)^{2} + (22)^{2} = 533 $

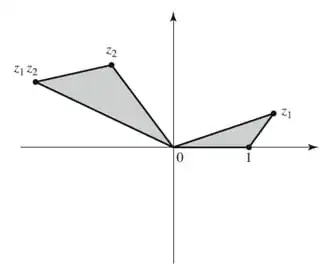

Note that during the process of this proof, we were taking products of two complex numbers. A geometric interpretation of that is shown below (reproduced from Complex Analysis. Bak, Newman). However, given that this is a number theoretic problem and the complex numbers cancel out to give integers, do complex numbers still help us give a geometric explanation?