Let $g$ be Riemann integrable on $[a,b]$, $f(x)=\int_a^x g(t)dt $ for $x \in[a,b]$.

Can I show that the total variation of $f$ is equal to $\int_a^b |g(x)| dx $?

Let $g$ be Riemann integrable on $[a,b]$, $f(x)=\int_a^x g(t)dt $ for $x \in[a,b]$.

Can I show that the total variation of $f$ is equal to $\int_a^b |g(x)| dx $?

$\smash{\rlap{\phantom{\Bigg\{}}}\newcommand{\Var}{\mathrm{Var}}$ Break up $g(t)=g_+(t)-g_-(t)$ where $$ g_+(t)=\left\{\begin{array}{}g(t)&\text{if }g(t)\ge0\\0&\text{if }g(t)<0\end{array}\right.\tag{1} $$ and $$ g_-(t)=\left\{\begin{array}{}0&\text{if }g(t)\ge0\\-g(t)&\text{if }g(t)<0\end{array}\right.\tag{2} $$ Define $$ f_+(x)=\int_a^xg_+(t)\,\mathrm{d}t\tag{3} $$ and $$ f_-(x)=\int_a^xg_-(t)\,\mathrm{d}t\tag{4} $$ Then, $f(x)=f_+(x)-f_-(x)$, where $f_+$ and $f_-$ are montonic increasing.

Note that $$ |g(t)|=g_+(t)+g_-(t)\tag{5} $$ and $$ \Var_a^b(f)=\Var_a^b(f_+)+\Var_a^b(f_-)\tag{6} $$ In light of $(5)$ and $(6)$, assume that $g(t)\ge0$ and $f$ is monotonic increasing.

For any partition $P=\{t_i:0\le i\le n\}$ where $a=t_0\le t_{i-1}< t_i\le t_n=b$, define $$ \Var_{\lower{3pt}P}(f)=\sum_{i=1}^n|f(t_i)-f(t_{i-1})|\tag{7} $$ Since $g(t)\ge0$ and $f$ is monotonic increasing, for any partition of $[a,b]$, $$ \begin{align} \Var_{\lower{3pt}P}(f) &=\sum_{i=1}^n|f(t_i)-f(t_{i-1})|\\ &=\sum_{i=1}^nf(t_i)-f(t_{i-1})\\ &=f(b)-f(a)\\ &=\int_a^bg(t)\,\mathrm{d}t\\ &=\int_a^b|g(t)|\,\mathrm{d}t\tag{8} \end{align} $$ Combining $(5)$, $(6)$, and $(8)$, we can remove the restriction on $g$: $$ \int_a^b|g(t)|\,\mathrm{d}t=\mathrm{Var}_a^b(f)\tag{9} $$ for all Riemann integrable $g$, as required.

Detailed Explanation of $\mathbf{(6)}$:

The idea is that the increases in $f_+$ and $f_-$ are disjoint because $g(t)$ cannot be both positive and negative.

Given a partition of $[a,b]$, $P=\{t_i:0\le i\le n\}$ and its intervals $I_i=(t_{i-1},t_i)$, define the upper and lower Riemann sums as $$ {\sum_P}^+g=\sum_{i=1}^n\sup_{t\in I_i}g(t)\;|I_i|\quad\text{and}\quad{\sum_P}^-g=\sum_{i=1}^n\inf_{t\in I_i}g(t)\;|I_i|\tag{10} $$ Choose an $\epsilon>0$. Since $g$ is Riemann integrable, there is a partition of $[a,b]$, $P=\{t_i\}$ , so that $$ {\sum_P}^+g_+-{\sum_P}^-g_+<\epsilon\quad\text{and}\quad{\sum_P}^+g_--{\sum_P}^-g_-<\epsilon\tag{11} $$ Let $\mathcal{I}_\pm$ be the subcollection of $\{I_i\}$ where $\sup\limits_{I_i}g_+>0$ and $\sup\limits_{I_i}g_->0$. Since only one of $g_+(t)$ or $g_-(t)$ can be non-zero, we have that for $I_i\in\mathcal{I}_\pm$ $$ \inf\limits_{I_i}g_+=\inf\limits_{I_i}g_-=0\tag{12} $$ which implies that the lower Riemann sums of $g_+$ and $g_-$ restricted to $\mathcal{I}_\pm$ must be $0$: $$ {\sum_{\mathcal{I}_\pm}}^-g_+={\sum_{\mathcal{I}_\pm}}^-g_-=0\tag{13} $$ Thus, $(11)$ and $(13)$ imply that the upper Riemann sums of $g_+$ and $g_-$ restricted to $\mathcal{I}_\pm$ must be small: $$ {\sum_{\mathcal{I}_\pm}}^+g_+<\epsilon\quad\text{and}\quad{\sum_{\mathcal{I}_\pm}}^+g_-<\epsilon\tag{14} $$ Estimates $(14)$ show that $$ \Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_\pm}(f_+)<\epsilon\quad\text{and}\quad\Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_\pm}(f_-)<\epsilon\tag{15} $$ Let $\mathcal{I}_+$ be the subcollection of $I_i$ where $\sup\limits_{I_i}g_-=0$ and $\mathcal{I}_-$ be the subcollection where $\sup\limits_{I_i}g_+=0$. Then, $$ \Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_-}(f_+)=0\quad\text{and}\quad\Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_+}(f)=\Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_+}(f_+)>\Var_{\lower{3pt}P}(f_+)-\epsilon\tag{16} $$ $$ \Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_+}(f_-)=0\quad\text{and}\quad\Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_-}(f)=\Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_-}(f_-)>\Var_{\lower{3pt}P}(f_-)-\epsilon\tag{17} $$ Combining $(16)$ and $(17)$ yields $$ \begin{align} \Var_{\lower{3pt}P}(f) &\ge\Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_+}(f)+\Var_{\lower{3pt}\mathcal{I}_-}(f)\\ &>\Var_{\lower{3pt}P}(f_+)+\Var_{\lower{3pt}P}(f_-)-2\epsilon\tag{18} \end{align} $$ Since we can refine $P$ and make $\epsilon$ as small as we want, $(18)$ shows that $$ \Var_a^b(f)\ge\Var_a^b(f_+)+\Var_a^b(f_-)\tag{19} $$ The opposite inequality is immediate, so we get $(6)$.

If $g$ is non-negative, $f$ is non-decreasing and the total variation is $f(b)-f(a)$ which coincides with $\int_a^b{|g(x)|}dx$, so the theorem is true.

For arbitrary $g$, write $g=g^+-g^-$, with at least one of $g^+(x)$ and $g^-(x)$ equal to 0.

Fix $\varepsilon>0$. There is a mesh $\delta^+>0$ such that for all partitions $a=x_0<\dots<x_n=b$ of $[a,b]$ finer than $\delta^+$ (i.e. $\max_i x_{i+1}-x_i\le\delta^+$), $$\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i-x_{i-1})\inf g^+([x_{i-1},x_i]) \ge \int_a^b{g^+(x)}dx - \varepsilon/2$$ We define $\delta^-$ symmetrically, and let $\delta=\min (\delta^+,\delta^-)$.

Now let's compute the total variation for a partition $x_0<\dots<x_n$ of $[a,b]$ finer than $\delta$: $$V=\sum_{i=1}^n |f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1})|$$ For any interval $I=[x_i,x_{i-1}]$, if $\inf g^+(I)>0$, then $g^+$ is always non-zero on this interval and $g^-$ must be identically zero. Then $$\begin{aligned} |f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1})| =&\int_I{g^+(x)}dx\\ \ge&(x_i-x_{i-1})\inf g^+([x_{i-1},x_i])\\ =&(x_i-x_{i-1})\inf g^+([x_{i-1},x_i]) + (x_i-x_{i-1})\inf g^-([x_{i-1},x_i]) \end{aligned}$$ The bound holds similarly when $\inf g^-(I)>0$. Finally when $\inf g^+(I)=\inf g^-(I)=0$, $$\begin{aligned} |f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1})| \ge&0\\ =&(x_i-x_{i-1})\inf g^+([x_{i-1},x_i]) + (x_i-x_{i-1})\inf g^-([x_{i-1},x_i]) \end{aligned}$$

So we can write $$V\ge \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i-x_{i-1})\inf g^+([x_{i-1},x_i]) + (x_i-x_{i-1})\inf g^-([x_{i-1},x_i])$$ and because the partition is finer than $\delta$: $$V \ge \left(\int_a^b{g^+(x)}dx - \varepsilon/2\right)+\left(\int_a^b{g^-(x)}dx - \varepsilon/2\right)$$ that is $$V \ge \int_a^b{|g(x)|}dx - \varepsilon$$

We also have the obvious upper bound $$V=\sum_{i=1}^n \left|\int_{x_{i-1}}^{x_i} {g(x)} dx\right|\le \sum_{i=1}^n \int_{x_{i-1}}^{x_i} {|g(x)|} dx = \int_a^b{|g(x)|}dx$$

Since this holds for all $\varepsilon$, the total variation (the upper bound of the total variation over all partitions) is precisely $\int_a^b{|g(x)|}dx$.

$\newcommand{\P}{\mathcal{P}[a,b]}\newcommand{\R}{\mathbb{R}}$ Let's to establish the notation first.

Let $\P$ the set of all the partitions $\Gamma=\{a=x_0\lt x_1\lt\ldots\lt x_m=b\}$ of $[a,b]$. For such a $\Gamma$, define $$|\Gamma|=\max_{i\in \{1,\ldots,m\}} x_i - x_{i-1}$$ and $$S_\Gamma[a,b]=\sum_{i=1}^m |f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1})|$$

We say that a function $h$ is of bounded variation on $[a,b]$ if $\{S_\Gamma[a,b]:\Gamma\in\P\}$ is bounded. In that case, $$V_f[a,b]=\sup\{S_\Gamma[a,b]:\Gamma\in\P\}.$$

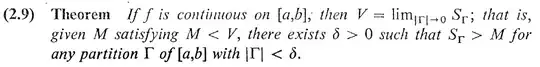

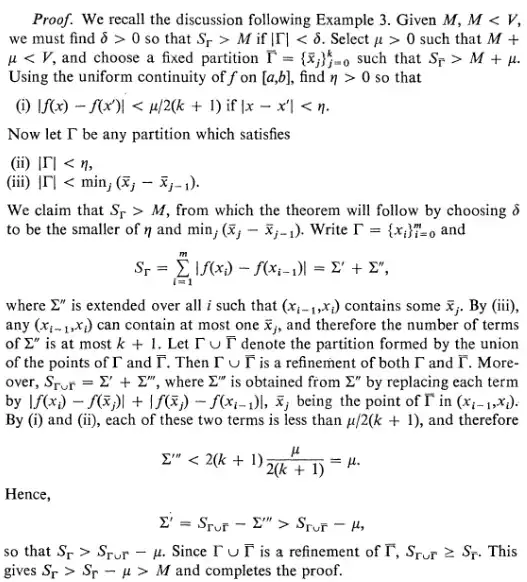

Now, consider the following theorem taken from Zygmund & Wheeden, Measure and Integral.

Provided that $g$ is Riemann integrable on $[a,b]$, the function $$f(x)=\int_a^x g(t)\ \mathbb{d}t$$ is continuous. For any partition $\Gamma=\{a=x_0\lt\ldots\lt x_m=b\}$ we have $$\begin{equation} \sum_{i=1}^m |f(x_i)-f(x_{i-1})|= \sum_{i=1}^m \left| \int_{x_{i-1}}^{x_i} g(t)\ \mathrm{d}t \right|\tag{1} \end{equation}$$ By the Theorem 2.9 cited above, it is enough to show that $$\lim_{|\Gamma|\to 0} \sum_{i=1}^m \left| \int_{x_{i-1}}^{x_i} g(t)\ \mathrm{d}t \right|=\int_a^b |g(t)|\ \mathrm{d}t$$ because in that case in view of (1) we get the desired result.

If we assume $g$ continuous on $[a,b]$ then $g$ is integrable on $[a,b]$ and therefore $$\begin{align*} \sum_{i=1}^m \left| \int_{x_{i-1}}^{x_i} g(t)\ \mathrm{d}t \right| &= \sum_{i=1}^m \left| g(\theta_i)(x_i-x_{i-1}) \right|\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^m |g(\theta_i)|(x_i-x_{i-1}) \end{align*}$$ for some $\theta_i\in (x_{i-1},x_i)$, so $$\lim_{|\Gamma|\to 0} \sum_{i=1}^m \left| \int_{x_{i-1}}^{x_i} g(t)\ \mathrm{d}t \right|=\lim_{|\Gamma|\to 0}\sum_{i=1}^m |g(\theta_i)|(x_i-x_{i-1})=\int_a^b |g(t)|\ \mathrm{d}t$$ as we want.

Another approach. Remember that for a Riemann integrable function on $[a,b]$ the Riemann and Lebesgue integrals over $[a,b]$ are the same.

Theorem 1. Let $f:\R\to\R$ be monotone increasing and finite on an interval $(a,b)$. Then $f$ has a measurable, nonnegative derivative $f'$ almost everywhere in $(a,b)$. Moreover, $$0\leq\int_a^b f'\leq f(b-)-f(a+).$$

Theorem 2. Let $f$ of bounded variation on $[a,b]$. Write $$V(x)=V_f[a,x].$$ Then $$V'(x)=|f'(x)|$$ for almost every $x\in [a,b]$.

Corollary 3. Let $f$ of bounded variation on $[a,b]$. Then $$\int_a^b |f'|\leq V_f[a,b].$$

Proof. Since $f$ is of bounded variation on $[a,b]$, by Theorem 2 we have $$\int_a^b |f'|=\int_a^b V',$$ since $V$ is increasing by Theorem 1. we get $$\int_a^b |f'|=\int_a^b V'\leq V(b)-V(a)=V(b)=V_f[a,b].$$

Theorem 4 (Lebesgue's Differentiation Theorem). Let $f\in L([a,b])$. Then $$\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}x}\int_a^x f(t)\ \mathrm{d}t=f(x)$$ for almost every $x\in [a,b]$.

Now, since $g$ is Riemann integrable, $g\in L[a,b]$. By the above Theorem $$f'(t)=g(t)$$ for almost every $t\in [a,b]$.

The estimate (already dealt with in this answer) $$S_\Gamma\leq \int_a^b |g|\quad \forall\Gamma\in \P$$ shows that indeed $f$ is of bounded variation on $[a,b]$. Moreover, it says that $$V_f[a,b]\leq\int_a^b |g|\tag{2}$$ Therefore Corollary 3 is applicable and by the above observation ($f'(t)=g(t)$ a.e. in $[a,b]$) we get $$\int_a^b |g|=\int_a^b |f'|\leq V_f[a,b],$$ in view of $(2)$ we conclude $$\int_a^b |g|=V_f[a,b]$$ as we wanted.

Just reading the definition in Wikipedia, I can give you some ideas:

$$V_a^b\left( f \right) = \mathop {\sup }\limits_P \sum\limits_{i = 0}^{{n_P} - 1} {\left| {f\left( {{x_{i + 1}}} \right) - f\left( {{x_i}} \right)} \right|} $$

where $\sup$ runs over the set of all partitions $P$ of $[a,b]$,

$$\mathcal P=\{P=\{x_0,\dots, x_{n_P}\}:P\text{ is a partition of }[a,b]\}$$

I assume $g$ is continuous in $[a,b]$. This means $f$ differentiable in $[a,b]$ and continuous, and we can apply the MVT, which means

$$f(x_{i+1})-f(x_i)=(x_{i+1}-x_i)f'(y_i)$$

where $y_i \in (x_i,x_{i+1})$. Thus the sum becomes:

$$V_a^b\left( f \right) = \mathop {\sup }\limits_P \sum\limits_{i = 0}^{{n_P} - 1} {\left| f'(y_i) \right||x_{i+1}-x_i|} $$

If $g$ is continuous then it is bounded, and therefore it is Riemann integrable.

Note that if $f(x)=\int_a^x g(t) dt$ then $f'(x)=g(x)$. Then the sum is

$$V_a^b\left( f \right) = \mathop {\sup }\left\{ \sum\limits_{i = 0}^{{n_P} - 1} {\left| g(y_i) \right||x_{i+1}-x_i|}:P=\{x_0,\dots,x_{n_P}\} \text{ is a partition of }[a,b] \right\}$$

One direction's pretty easy, for a partition $a:= x_0 < x_1 < \ldots < b := x_n$, we have $$\sum |f(x_{i+1}) - f(x_i)| = \sum |\int_{x_i}^{x_{i+1}} g(t)dt| \leqslant \sum \int_{x_i}^{x_{i+1}} |g(t)|dt = \int_a^b |g(t)|dt$$So total variation is bounded above by this.