In the definition of a convex cone, given that $x,y$ belong to the convex cone $C$,then $\theta_1x+\theta_2y$ must also belong to $C$, where $\theta_1,\theta_2 > 0$. What I don't understand is why there isn't the additional constraint that $\theta_1+\theta_2=1$ to make sure the line that crosses both $x$ and $y$ is restricted to the segment in between them.

-

2The cone, by definition, contains rays, i.e. half-lines that extend out to the appropriate infinite extent. Adding the constraint that $\theta_1 + \theta_2 = 1$ would only give you a convex set, it wouldn't allow the extent of the cone. – postmortes Sep 15 '15 at 17:07

-

2If $\theta_1,\theta_2 \geq 0 $ this means in particular that all $\theta_1,\theta_2$ with $\theta_1+\theta_2 =1$ are also included – asterisk Sep 15 '15 at 17:09

-

@postmortes But how will you check for convexity if you don't? Wouldn't the set then have to be affine to satisfy that condition? – Undertherainbow Sep 15 '15 at 17:11

-

1@postmortes I mean that if you don't restrict the line to the segment in between them, then the whole line would have to be in the set, so it would not just be convex, it would have to be an affine set to satisfy those conditions, right? I don't know. – Undertherainbow Sep 15 '15 at 17:15

-

It won't be an affine set unless the cone includes points either side of 0 (affine sets contain lines that go from postive infinity to negative infinity. @asterisk's comment points out that your cone will still be convex: pick any two points in it and all points on the line between them must lie in the cone, hence it is convex. Think about the positive orthant (i.e. ${x\in\mathbb{R}^n: x_i\geq0}$) – that's a convex cone. – postmortes Sep 15 '15 at 17:18

-

@postmortes What about the line between two points on opposite sides of the cone? Unless we restrict it to the segment between them, the whole line won't be in the cone. – Undertherainbow Sep 15 '15 at 17:23

-

That's not true :) Let's take $x$ to lie on one edge of the cone and $y$ to lie on the other edge (e.g. x=(1,0) and y = (0,1) in $\mathbb{R}^2$, using the non-negative orthant as our cone). Then $\theta_1 x + (1-\theta_1)y$ lies in the cone for $0\leq\theta_1\leq1$ but to get a point outside of the cone either $\theta_1$ or $1-\theta_1$ must go negative -- which isn't allowed by the definition of the cone. Think of vector addition: that's how all your points are staying in the cone – postmortes Sep 15 '15 at 17:34

-

@postmortes Oh yes! Thank you for your help! I really appreciate it :) – Undertherainbow Sep 15 '15 at 17:38

-

1@Undertherainbow A good explanation is given here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QV5qtTq1Tro in minute 16:28 .. hope this helps :) – Ahmad Bazzi Feb 12 '19 at 11:48

3 Answers

It is sufficient that $\theta_1 x+ \theta_2y \in C, \theta_1,\theta_2\ge 0$ implies $C$ is convex, which includes the case $\theta x+(1-\theta)y,\theta \in [0,1]$.

Conversely, is it necessary? Say that a cone is convex implies $\theta_1 x+ \theta_2y \in C, \theta_1,\theta_2\ge 0$. Convexity means $\theta x+(1-\theta)y \in C$. For a cone, $x\in C$ requires $\lambda x \in C, \lambda \ge 0$. We can then replace $x,y$ with $\lambda x,\lambda \ge 0$ and $\mu y,\mu \ge 0$ that both belong to $C$, like $\theta \lambda x+(1-\theta)\mu y \in C$. Since $\lambda,\mu$ can be any non-negative real number, we can conclude that $\theta_1 x +\theta_2 y \in C, \theta_1, \theta_2 \ge 0$ is necessary, under the convexity condition.

Given that $x, y$ belong to the convex cone $C$, then $θ_1x+θ_2y$ must also belong to C, where $θ_1,θ_2 \geq 0 $.

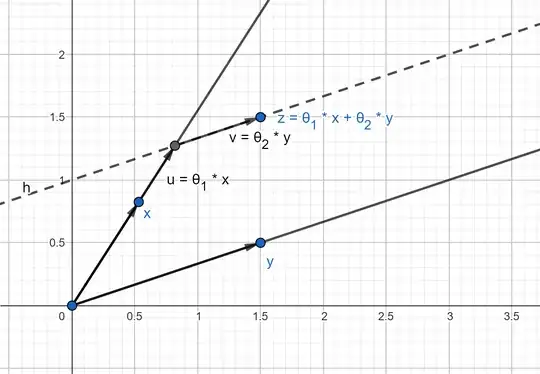

Some visualization helped me to understand the equation. As you can see below, a point z within the convex cone can be represented as a linear combination of x and y with non-negative coefficients $θ_1$ and $θ_2$.

To be able to reach all points (i.e. write them as linear combinations of x and y with with non-negative coefficients $θ_1$ and $θ_2$) within the boundaries of the convex cone, we need to vary $θ_1$ and $θ_2$ without the constraint that they sum to 1.

We are given that $x$ and $y$ belong to the convex cone C. Therefore, $\theta_1 x \in C$ and $\theta_2 y \in C$ for any $\theta_1,\theta_2 > 0$. It is also possible to prove the condition $\theta_1 x + \theta_2 y \in C$ directly.

First note that, for any $0 < \theta < 1$, it is also true that $\theta \theta_1 x \in C$ and $(1 - \theta) \theta_2 y \in C$ since, for such a $\theta$, $0 < 1 - \theta < 1$.

Now, since $C$ is convex, a convex combination of $\theta \theta_1 x$ and $(1 - \theta) \theta_2 y$ also lies in C. More specifically, $(1 - \theta) (\theta \theta_1 x) + \theta ((1 - \theta) \theta_2 y) \in C$. Here, the coefficients of $(\theta \theta_1 x)$ and $ ((1 - \theta) \theta_2 y)$ sum to 1 due to which it is possible to state this conclusion.

Let $\gamma = (1 - \theta) (\theta \theta_1 x) + \theta ((1 - \theta) \theta_2 y) \in C$. On rearrangement we find that $\gamma = \theta(1 - \theta)(\theta_1 x + \theta_2 y)$. Now, we know that $\theta(1 - \theta) > 0$. Hence, $\alpha = \frac{1}{\theta(1 - \theta)} > 0$. Since, C is a cone, $\alpha \gamma \in C$. It is now straightforward to verify that $\theta_1 x + \theta_2 y \in C$.

- 11