More generally, suppose for some $S,P$ we're given a rational solution

$(a_0,b_0,c_0)$ of the Diophantine equation

$$

E = E_{S,P}:

\quad

a+b+c = S,

\ \

abc = P.

$$

Then, as long as $a,b,c$ are pairwise distinct,

we can obtain a new solution $(a_1,b_1,c_1)$ by applying the transformation

$$

T\bigl((a,b,c)\bigr) = \left(

-\frac{a(b-c)^2}{(a-b)(a-c)} \, ,

-\frac{b(c-a)^2}{(b-c)(b-a)} \, ,

-\frac{c(a-b)^2}{(c-a)(c-b)}

\right).

$$

Indeed, it is easy to see that the coordinates of $T(a,b,c)$ multiply to $abc$;

that they also sum to $a+b+c$ takes only a bit of algebra.

(This transformation was obtained by regarding $abc=P$ as a cubic curve

in the plane $a+b+c=S$, finding the tangent at $(a_0,b_0,c_0)$,

and computing its third point of intersection with $abc=P$;

see picture and further comments below.)

We can then repeat the procedure, computing

$$

(a_2,b_2,c_2) = T\bigl((a_1,b_1,c_1)\bigr),

\quad

(a_3,b_3,c_3) = T\bigl((a_2,b_2,c_2)\bigr),

$$

etc., as long as each $a_i,b_i,c_i$ are again pairwise distinct.

In our case $S=P=6$ and we start from $(a_0,b_0,c_0) = (1,2,3)$,

finding

$(a_1,b_1,c_1) = (-1/2, 8, -3/2)$,

$(a_2,b_2,c_2) = (-361/68, -32/323, 867/76)$,

$$

(a_3,b_3,c_3) = \left(

\frac{79790995729}{9885577384}\, ,\

-\frac{4927155328}{32322537971}\, ,\

-\frac{9280614987}{24403407416}\,

\right),

$$

"etcetera".

As with the recursive construction given by Tito Piezas III,

the construction of $T$ via tangents to a cubic is an example of

a classical technique that has been incorporated into the modern

theory of elliptic curves but does not require explicit

delving into this theory. Also as with TPIII's construction,

completing the proof requires showing that the iteration

does not eventually cycle. We do this by showing that

(as suggested by the first three steps) the solutions $(a_i,b_i,c_i)$

get ever more complicated as $i$ increases.

We measure the complexity of a rational number by writing it as $m/n$

in lowest terms and defining a "height" $H$ by $H(m/n) = \sqrt{m^2+n^2}$.

Using the defining equations of $E_{S,P}$, we eliminate $b,c$ from

the formula for the first coordinate of $T\bigl( (a,b,c) \bigr)$,

and likewise for each of the other two coordinates, finding that

$$

T\bigl( (a,b,c) \bigr) = (t(a),t(b),t(c)) \bigr)

$$

where

$$

t(x) := -\frac{x^2(x-S)^2 - 4Px}{x^2(2x-S)+P}.

$$

We find that the numerator and denominator are relatively prime

as polynomials in $x$, unless $P=0$ or $P=(S/3)^3$, when $E_{S,P}$

is degenerate (obviously so if $P=0$, and with an isolated double point

at $a=b=c=S/3$ if $P=(S/3)^3$). Thus $t$ is a rational function of degree $4$,

meaning that

$$

t(m/n) = \frac{N(m,n)}{D(m,n)}

$$

for some homogeneous polynomials $N,D$ of degree $4$ without common factor.

We claim:

Proposition. If $f=N/D$ is a rational function of degree $d$

then there exists $c>0$ such that $H(t(x)) \geq c H(x)^d$ for all $x$.

Corollary: If $d>1$ and a sequence $x_0,x_1,x_2,x_3,\ldots$

is defined inductively by $x_{i+1} = f(x_i)$, then $H(x_i) \rightarrow \infty$

as $i \rightarrow \infty$ provided some $H(x_i)$ is large enough, namely

$H(x_i) > c^{-1/(d-1)}$.

Proof of Proposition: This would be clear if we knew that the fraction

$f(m/n) = N(m,n)/D(m,n)$ must be in lowest terms, because then we could take

$$

c = c_0 := \min_{m^2+n^2 = 1} \sqrt{N(m,n)^2 + D(m,n)^2}.

$$

(Note that $c_0$ is strictly positive, because it is the minimum value of

a continuous positive function on the unit circle, and the unit circle

is compact.) In general $N(m,n)$ and $D(m,n)$ need not be relatively prime,

but their gcd is bounded above: because $N,D$ have no common factor,

they have nonzero linear combinations of the form $R_1 m^{2d}$ and $R_2 n^{2d}$,

and since $\gcd(m^{2d},n^{2d}) = \gcd(m,n)^{2d} = 1$ we have

$$

\gcd(N(m,n), D(m,n)) \leq R := \text{lcm} (R_1,R_2).

$$

(In fact $R = \pm R_1 = \pm R_2$, the common value being

$\pm$ the resultant of $N$ and $D$; but we do not need this.)

Thus we may take $c = c_0/R$, QED.

For our degree-$4$ functions $t$ associated with $E_{S,P}$ we compute

$R = P^2 (27P-S^3)^2$, which is $18^4$ for our $S=P=6$; and we calculate

$c_0 > 1/12$ (the minimum occurs near $(.955,.3)$). Hence the sequence

of solutions $(a_i,b_i,c_i)$ is guaranteed not to cycle once some

coordinate has height at least $(12 \cdot 18^4)^{1/3} = 108$.

This already happens for $i=2$,

so we have proved that $E_{6,6}$ has infinitely many rational solutions.

$\Box$

The same technique works with TPIII's recursion, which has $d=9$.

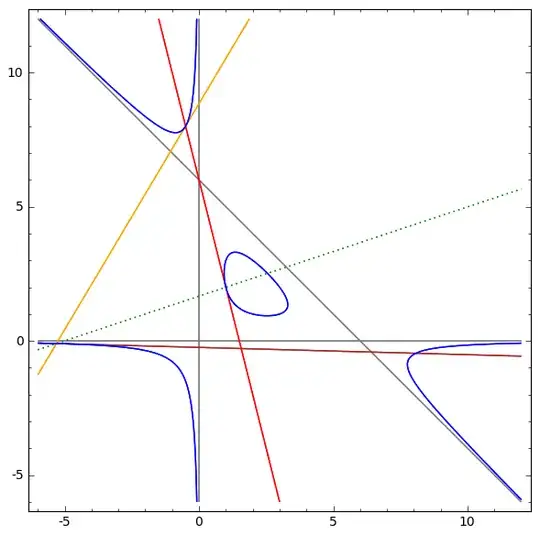

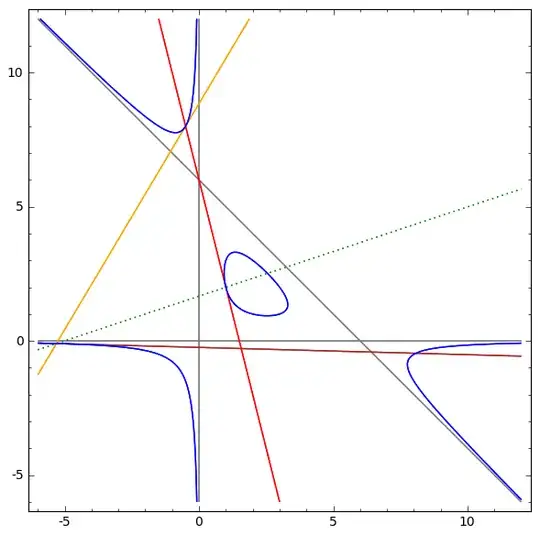

The following Sage plot shows:

in $\color{blue}{\text{blue}}$, the curve $E_{6,6}$, projected to the

$(a,b)$ plane (with both coordinates in $[-6,12]$);

in $\color{gray}{\text{gray}}$, the asymptotes $a=0$, $b=0$, and $c=0$;

and in $\color{orange}{\text{orange}}$, $\color{red}{\text{red}}$, and

$\color{brown}{\text{brown}}$, the tangents to the curve at

$(a_i,b_i,c_i)$ that meet the curve again at $(a_{i+1},b_{i+1},c_{i+1})$,

for $i=0,1,2$:

(source: harvard.edu)

Further solutions can be obtained intersecting $E$ with the line

joining two non-consecutive points; this illustrated by the

dotted $\color{green}{\text{green}}$ line, which connects the

$i=0$ to the $i=2$ point, and meets $E$ again in a point

$(20449/8023, 25538/10153, 15123/16159)$ with all coordinates positive.

In the modern theory of elliptic curves, the rational points

(including any rational "points at infinity", here the asymptotes)

form an additive group, with three points adding to zero iff they are

the intersection of $E$ with a line (counted with multiplicity).

Hence if we denote our initial point $(1,2,3)=(a_0,b_0,c_0)$ by $P$,

the map $T$ is multiplication by $-2$ in the group law, so the

$i$-th iterate is $(-2)^i P$, and $(20449/8023, 25538/10153, 15123/16159)$

is $-(P+4P) = -5P$. Cyclic permutations of the coordinates is translation

by a 3-torsion point (indeed an elliptic curve has a rational 3-torsion

point iff it is isomorphic with $E_{S,P}$ for some $S$ and $P$),

and switching two coordinates is multiplication by $-1$. The iteration

constructed by Tito Piezas III is multiplication by $\pm 3$ in the

group law; in general, multiplication by $k$ is a rational function

of degree $k^2$.

$$\left(\frac{5^2}{3\cdot7},6\cdot\frac{3^2}{5\cdot7},\frac{7^2}{3\cdot5}\right)$$

and

$$\left(-2\cdot\frac{4^2}{17\cdot19},-\frac{19^2}{4\cdot17},3\cdot\frac{17^2}{4 \cdot19}\right);,$$

so one could try to look for solutions of the form

$$\left(s\cdot\frac{x^2}{yz},t\cdot\frac{z^2}{xy},\frac6{st}\cdot\frac{y^2}{xz} \right);,$$

possibly with $z=y+2$ and/or $y$ and $z$ prime.

– joriki Aug 05 '15 at 04:42