Let $Q(n,k)$ be the number of ways in which we can connect sets of $k$ vertices in a given perfect $n$-gon such that no two lines intersect at the interior of the $n$-gon and no vertex remains isolated.

Intersection of the lines outside the $n$-gon is acceptable. Obviously, $k|n$, and $n$ can't be prime because otherwise there will be dots left unconnected. The $n$-gon itself is an acceptable solution to a connection of $n$ vertices, and in the case of $k>2$, these aren't lines, but a set of connected lines, a sort of a network formed by connected planar graphs with straight edges with $k$ vertices, which are required to be vertices of the $n$-gon itself.

There must always be $S =\frac nk$ sets of lines. For $k=2$, there are exactly $\frac nk$ lines, and for $k>2$, there are exactly $\frac nk$, not lines but sets of such connected planar graphs.

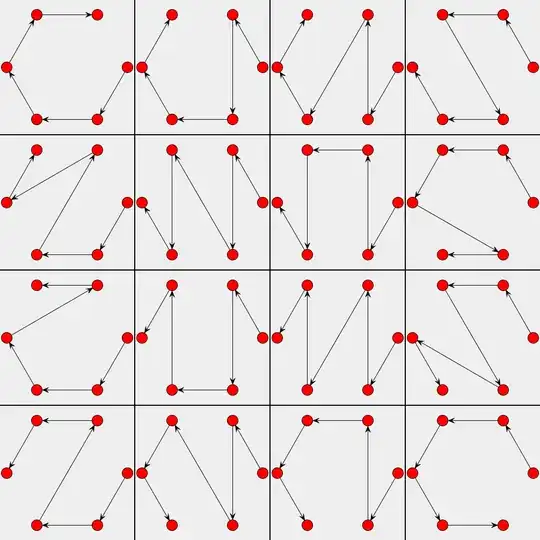

Take for example $Q(6,2)$. We have a perfect hexagon. By brute-forcing with pencil and paper, I found that there are 5 ways to connect sets of 2 vertices (dots) such that no two lines intersect inside the hexagon. Hence, $Q(6,2) = 5$.

The following image depicts the case of $Q(6,2)$:

I know for sure that an elegant solution exists for $k=2$, but I can't figure it out. For generality I ask about any amount of $k$ dots.

It's also extremely important to note we're not dividing the $n$-gon into $k$-gons, but connecting paths between $k$ nodes/vertices/dots.

Now let's move one step further:

Let $U(n,k)$ be the number of unique ways to connect sets of $k$ dots in a perfect $n$-gon, such that no two lines intersect, and rotational symmetry is neglected, i.e, every possible arrangement is unique and can't be formed by rotating or flipping another arrangement in any way. $U(6,2)=2$. Note that $U(6,2)=2$ because the arrangements of the first line in the image are not unique, and can be formed by rotating one another. The same happens for the second line of arrangements. This results in only 1 unique arrangement for each line. Hence $U(6,2)=2$.

I'm pretty clueless about both functions $U$ and $Q$, and I couldn't derive an algorithm or formula to any of them. Hence I'm posting this here.

I'm pretty sure there's a pure combinatorial approach to this problem, perhaps involving Polya's Enumeration Theorem (PET). Is there an elegant solution to these functions? Can they even be solved for $k>2$?

Any light shed on any of the functions will be very much appreciable, as I haven't been successful in deriving a formula for any of them.

EDIT - Temporary Solutions + Relevant questions AND progress

$$Q(n,2) = C_{n \over 2}\quad\text{where}\quad C_n = \frac{1}{n+1} {2n\choose n}$$ And $C_n$ denotes the $n$'th Catalan number.

Now let us denote $W(n) = U(n,2)$. Can you find a formula for $W(n)$? Perhaps a connection between $Q(n,2)$ and $W(n)$?

Another EDIT: (2)

$$Q(k,k) = k\cdot 2^{k-3}$$

EDIT 3

It seems like in general, $Q(n,3)$ is given here: https://oeis.org/search?q=3%2C27%2C324&sort=&language=english&go=Search

Perhaps generalization to higher powers will result in the general $Q(n,k)$ function..

EDIT 4

Here is a small table of values for $Q(n,k)$, which seems to be correct, provided by fabian's algorithm: (Table is in the form $Q(x\cdot k,k)$)

$$ \begin{array}{c|rrrrr} {_k\,\backslash\, ^n} & k & 2k & 3k & 4k & 5k \\ \hline 2 & 1 & 2 & 5 & 14 & 42\\ 3 & 3 & 27 & 324 & 4455 & 66339\\ 4 & 8 & 256 & 11264 & 573440 & 31752192\\ 5 & 20 & 2000 & 280000 & 45600000 & 8096000000\\ 6 & 48 & 13824 & 5640192 & 2686058496 & 1396580548608\\ \end{array} $$

EDIT 5 - $Q(n,k)$ SOLVED

As beautifully found and explained by @CuddlyCuttlefish in his answer, the formula for $Q(n,k)$ is as follows: $$Q(n,k) = \frac{(n)_{\frac{n}{k}-1}}{\left(\frac{n}{k}\right)!}\cdot (k\cdot 2^{k-3})^{\frac{n}{k}} \quad\text{where}\quad (n)_j = n(n-1)...(n-(j-1))$$

And $(n)_j$ is the falling factorial, defined as above.

Now moving to $U(n,k)$

Now it only remains to find a formula or an algorithm for $U(n,k)$. Personally I think it has to do with Polya's Enumeration Theorem and Burnside's lemma, combined with the cycle-index of the symmetric group, $Z(S_n)$. I've touched upon something related to that, and thus I think it's related. I'm not 100% sure but my instincts tell me it's related.

EDIT 6

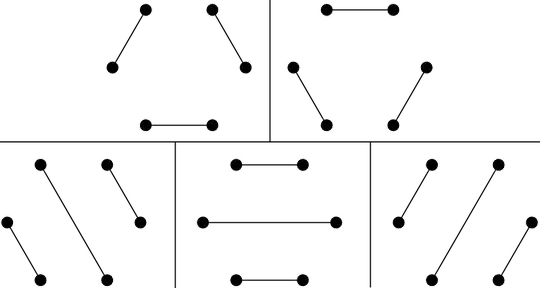

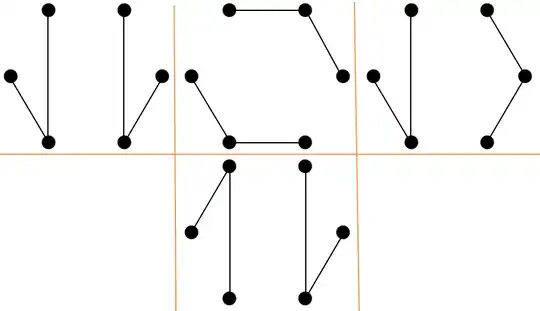

In order to make it clear, I'm hereby adding a picture to describe the case of $U(6,3)$ and by that to clarify better what $U(n,k)$ means.

$U(6,3)=4$, as shown in the picture above (@Marko Riedel has pointed out an additional arrangement which I had previously missed). There are four unique arrangements to connect sets of 3 vertices such that no vertice remains isolated, no lines intersect at the interior of the hexagon, and each arrangement is unique and can't be formed by rotating or flipping any other arrangement.

There are two unique path-types, one that is introduced by connecting 3 adjacent vertices ($p_1$), and another that connects 2 vertices with a little "jump", and the third vertice is then adjacent ($p_2$).

Hope it makes things a bit clearer..

EDIT 7

As provided by @Marko Riedel's algorithm, $U(n,3)$ sequence starts as follows:

$$1, 4, 22, 201, 2244, 29096, 404064, 5915838,\ldots$$

Computation was very rough, and calculation times were long. That's about as efficient as it gets, as of now. Producing more values just consumes either too much memory, time or both. Refer to Marko Riedel's answers for more sequences and further explanations. Also if anybody can verify the above it would be great.