Using the Weierstrass Normal form, let's try to understand the elliptic integral

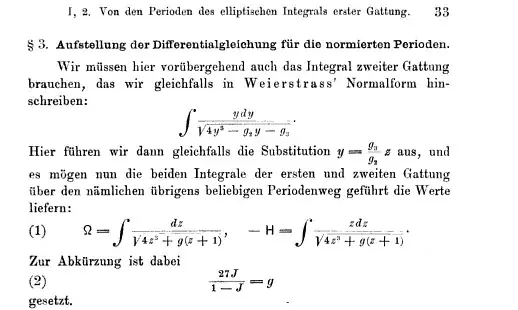

$$ \int \frac{dy}{\sqrt{4y^3 - g_2 y - g_3}} $$

In order to reduce the number of parameters, Fricke and Klein do a change of variables $y = \frac{g_2}{g_3}z$. The elliptic curve has two basic periods

$$ \Omega = \int \frac{dz}{\sqrt{4z^3 + g(z+1)}}

\text{ and }

-H = \int \frac{z\,dz}{\sqrt{4z^3 + g(z+1)}}

$$

This new parameter $g$ is basically the $J$-invariant in disguise. $\frac{27 J}{1-J} = g $. Let's just call the denominator $R = \sqrt{\dots}$.

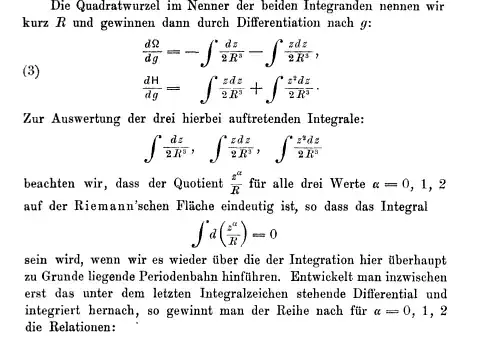

What happens if we change $g$? Let's differentiate under the integral sign:

\begin{eqnarray}

\frac{d\Omega}{dg} &=& - &\int \frac{dz}{2R^3} & - &\int \frac{z \, dz}{2R^3}\\

\frac{dH}{dg} &=& & \int \frac{z \, dz}{2R^3} &+& \int \frac{z^2 \, dz}{2R^3}

\end{eqnarray}

These are called the Picard-Fuchs equations. In modern language, this is an instance of the Gauss-Manin connection.

The integral of any derivative along a closed path on the elliptic curve is going to be zero.

$$ \int d\left(\frac{z^a}{R}\right) =

\int \frac{a z^{a-1}}{R} - \int \frac{z^a(12 z^2 + g)}{2R^3}

= 0 \tag{$\ast$}$$

The first step says the derivative and integral are inverse operations - the fundamental theorem of calculus. For a closed path the two endpoints are the same so the integral is zero. For the second step use the quotient rule for derivatives and the definition of R as the denominator.

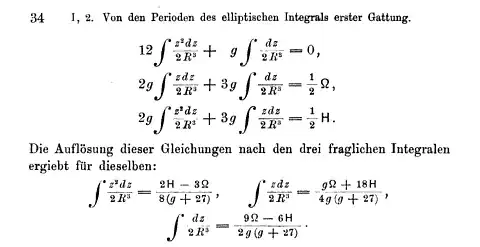

The first relation comes from setting $a = 0$ without any changes. The second and third relations start from setting $a = 1,2$ with some extra manipulation.

EDIT Yeah, they fall out of $R^2 = 4z^3 + g(z+1)$ and the definition of the periods $\Omega, H$.

Fricke and Klein solve for the periods and ultimately find the differential equation the period $\Omega$ satisfies in terms of the elliptic curve invariant $J$:

$$ \frac{d^2 \Omega}{dJ^2} +

\frac{1}{J} \cdot \frac{d \Omega}{dJ} + \frac{\frac{31}{144}J- \frac{1}{36}}{J^2(J-1)^2}\Omega = 0$$

When is $\oint \neq 0$ ?

The fundamental theorem of calculus says: $\int_a^b F'(x) \, dx = F(b) - F(a)$ so we integrate along a closed path, $a = b$ so the integral should be $F(b) - F(a) = 0$. Yet,

$$ \int_{|z|=1} \frac{dz}{z} = 2\pi i \neq 0 $$

What goes wrong is that $\frac{1}{z}$ is not holomorphic on $\mathbb{C}$, it is only holomorphic on $\mathbb{C} \backslash \{0\}$. By removing the one point we no longer have a plane, but a punctured plane. The circle $|z| = 1$ moves around this puncture and therefore integrating has a residue.

Another important issue is $\frac{1}{\sqrt{z}}$. The problem here is as we move around the unit circle from $1$ back to itself, the square roots go to $-1$.

$$ \sqrt{1} = \color{blue}{\mathbf{1}} \to \sqrt{i} = \mathbf{\tfrac{\color{blue}{1+i}}{\color{blue}{\sqrt{2}}}} \to \sqrt{-1} = \mathbf{\color{blue}{i}}\to \sqrt{-i} = \mathbf{\tfrac{\color{blue}{1-i}}{\color{blue}{\sqrt{2}}}} \to \sqrt{1} = -\mathbf{\color{green}{1}}$$

Basically every number has two square roots except for $0$, therefore the riemann surface $\{ (z, \pm \sqrt{z}): z \in \mathbb{C} \}$ has branching at $0$.

Using the identity $(\ast)$ with $a=1$ we can solve the 2nd identity.

\begin{eqnarray} \frac{1}{2}\Omega = \frac{1}{2}\int \frac{dz}{R}

= \frac{1}{2}\int \frac{R^2 }{R^3 } dz

&=& \frac{1}{2}\int \frac{4z^3 + g(z+1) }{R^3 } dz \\

&=& \frac{1}{2}\int \frac{4z^3 + g(z+1) + (-4z^3 + g(z+2))}{R^3 } dz \\

&=& 2g \int \frac{ z \, dz}{2R^3 } + 3g \int \frac{ dz}{2R^3 } \end{eqnarray}

Using the identity $(\ast)$ with $a=2$ we can solve the 3rd identity.

\begin{eqnarray} \tfrac{1}{2}H = -\tfrac{1}{2}\int \frac{z}{R} \, dz

= -\frac{1}{2}\int \frac{z R^2}{R^3} \, dz

&=& - \frac{1}{2}\int \frac{z(4z^3 + g(z+1)) }{R^3 } dz \\

&=& -\frac{1}{2}\int \frac{ -g(3z^2 + 4z) + g(z+1)z }{R^3 } dz \\

&=& 2g \int \frac{ z^2 \,dz }{2R^3 }

+ 3g\int \frac{ z \,dz}{2R^3 } \end{eqnarray}