When finding the orthogonal projection for this problem, why were those vectors added? Aren't the vectors normally subtracted for Gram-Schmidt and finding projections?

Also, how do you carry out the Gram Schmidt process for doing part (a)?

When finding the orthogonal projection for this problem, why were those vectors added? Aren't the vectors normally subtracted for Gram-Schmidt and finding projections?

Also, how do you carry out the Gram Schmidt process for doing part (a)?

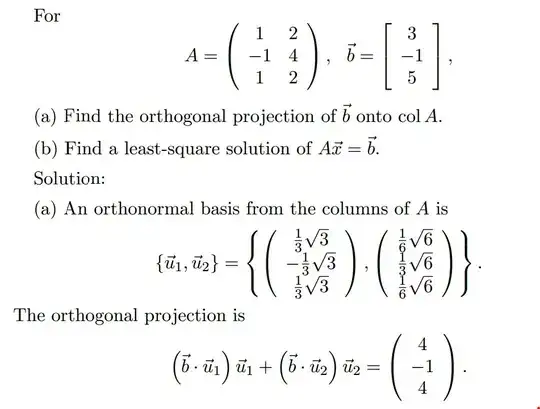

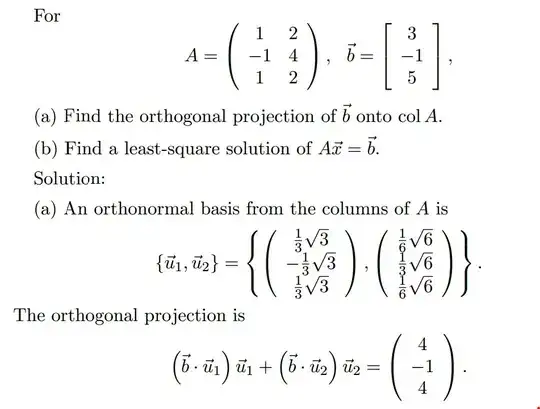

The column space of $A$ is $\operatorname{span}\left(\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ -1 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}, \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 4 \\ 2 \end{pmatrix}\right)$.

Those two vectors are a basis for $\operatorname{col}(A)$, but they are not normalized.

NOTE: In this case, the columns of $A$ are already orthogonal so you don't need to use the Gram-Schmidt process, but since in general they won't be, I'll just explain it anyway.

To make them orthogonal, we use the Gram-Schmidt process:

$w_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ -1 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}$ and $w_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 4 \\ 2 \end{pmatrix} - \operatorname{proj}_{w_1} \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 4 \\ 2 \end{pmatrix}$, where $\operatorname{proj}_{w_1} \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 4 \\ 2 \end{pmatrix}$ is the orthogonal projection of $\begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 4 \\ 2 \end{pmatrix}$ onto the subspace $\operatorname{span}(w_1)$.

In general, $\operatorname{proj}_vu = \dfrac {u \cdot v}{v\cdot v}v$.

Then to normalize a vector, you divide it by its norm:

$u_1 = \dfrac {w_1}{\|w_1\|}$ and $u_2 = \dfrac{w_2}{\|w_2\|}$.

The norm of a vector $v$, denoted $\|v\|$, is given by $\|v\|=\sqrt{v\cdot v}$.

This is how $u_1$ and $u_2$ were obtained from the columns of $A$.

Then the orthogonal projection of $b$ onto the subspace $\operatorname{col}(A)$ is given by $\operatorname{proj}_{\operatorname{col}(A)}b = \operatorname{proj}_{u_1}b + \operatorname{proj}_{u_2}b$.

Questions (a) and (b) turn out to be the same. By definition, the least squares solution is the $\DeclareMathOperator{\argmin}{\arg\!\min} \argmin_x \Vert Ax-b \Vert_2$. It's easy to prove that the minimum is attained for the orthogonal projection, i.e. for $x:(Ax-b)\perp col(A)$, or in matrix notation, $$ A^t(Ax-b)=A^tAx-A^tb=0 $$ If the columns of $A$ are linearly independent, the solution is $$x=(A^t A)^{-1}A^tb$$ It is both (b) the least squares solution and (a) the coordinates of the orthogonal projection in the basis of the columns-vectors of $A$, $Ax$ being the same vector given in the standard basis of the ambient space.