I am surprised that both answers, this and this, contain errors concerning the interpretation and meaning of p-values in a frequentist hypothesis testing framework.

Firstly, p-values are conditional probabilities. Thus, any interpretation lacking a condition is inherently flawed. Here are common mistakes, taken directly from Haller & Krauss (2002):

- "The improbability of observed results being due to error.

- "The probability that an observed difference is real."

- "If the probability is low, the null hypothesis is improbable."

- "The statistical confidence ... with odds of 95 out of 100 that the observed difference will hold up in investigations."

- "The degree to which experimental results are taken 'seriously'."

- "The danger of accepting a statistical result as real when it is actually due only to error."

- "The degree of faith that can be placed in the reality of the finding”

- "The investigator can have 95 percent confidence that the sample mean actually differs from the population mean."

Although these mistakes are understandable, they reflect questions that frequentist methods don’t directly answer, such as:

- What is the probability that the null hypothesis is true ?

- What is the probability that the result is....?

- The p-value proves that .....

The frequentist framework does not confirm any of these statements.

As already mentioned p-values are conditional probabilities. So any statement./ definition / interpretation that does not contain wording such as:

- ".....given that ..", or

- "....provided that......", or

- "....assuming that......",

and things like that, are wrong. Even if someone does have the correct understanding, it is very easy to get tripped up by the wording, For that reason I think it is far better to work with some simple algebra instead. So, let's do a little bit of maths.

The general setup is that we have some observed data, let's call it $\mathcal{D}$. In reality, it is the test statistic which is computed from the data, rather than the data themselves. Then we need a null hypothesis, let's call that $\mathcal{H_0}$, which could be something like: the difference between the means of two populations is zero. Then, the p-value is:

$$\mathcal{P}(\mathcal{D} \mid \mathcal{H_0})$$

which represents the probability of obtaining data at least as extreme as what we observed, assuming the null hypothesis $\mathcal{H_0}$ is true. Let's just dwell on that for a few moments. This means that we assume that the null hypothesis is true, and under that condition the p-value is the probability of observing data at least as extreme as that which we did observe. And that is pretty much it. We can, of course, come up with wording that might be useful for a non-technical audience, something along the lines of the comment on the OP by @Dave:

"The p-value, loosely speaking, is the probability of getting the observations you got if the null hypothesis is true. Thus, the low p-value is evidence against the null hypothesis."

However I would advise caution because it is very easy to get tripped up by the wording which can be misleading.

For further reason I highly recommend several threads over at CrossValidated:

ASA discusses limitations of p--values - what are the alternatives?

Interpretation of p-value in hypothesis testing

Understand a statement about P value

How much do we know about p-hacking "in the wild"?

Is it wrong to refer to results as being "highly significant"?

When to use Fisher versus Neyman-Pearson framework?

Are smaller p-values more convincing?

Frequentist properties of p-values in relation to type I error

Is the exact value of a 'p-value' meaningless?

Who first used/invented p-values?

What about the "p-value" of the non-null hypothesis?

Is p-value essentially useless and dangerous to use?

References:

Haller, H., & Krauss, S. (2002). Misinterpretations of significance: A problem students share with their teachers. Methods of psychological research, 7(1), 1-20.

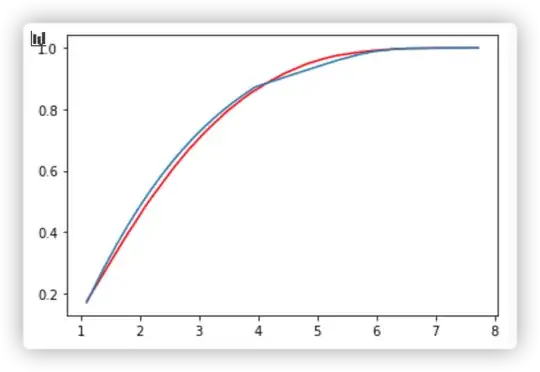

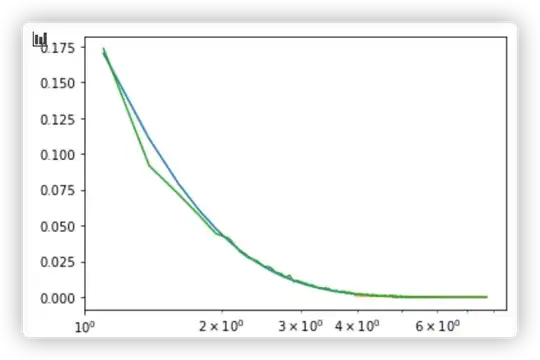

, but when I use KS-test to test the model, I got a low p-value,1.2e-4, definitely I should reject the model.

, but when I use KS-test to test the model, I got a low p-value,1.2e-4, definitely I should reject the model.