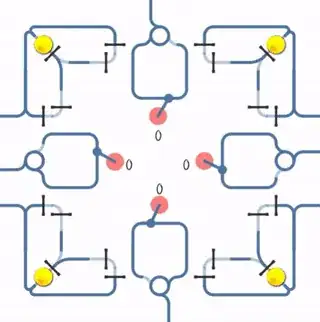

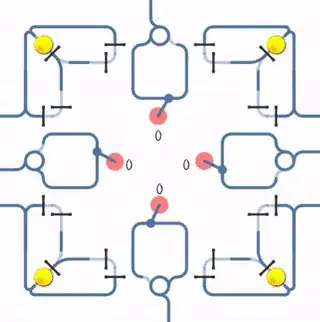

I created this simulation of the dining philosophers problem, but did not manage to initialize it with four philosophers without running into a deadlock:

*Philosophers are represented by black beads. They think when running in small circles and eat when running in bigger circles. Forks are represented by yellow beads. The number of meals are counted.

Might it be the case that for $N=4$ participating philosophers a deadlock must inevitably be reached? Or can a situation be described in which four philosophers can eat for ever and ever?

I am looking for a quantitative model and analysis of the dining philosophers problem.

Let $N$ be the number of philosophers. Let the problem be implemented as an algorithm that takes as inputs the set $T_k$ of partial functions $t: [N] \rightarrow [k]$ with $t(i)$ being the point in time when philosopher $i$ starts trying to pick the fork to his left (maybe never). The algorithm stops when it detects a deadlock or an oscillating state in which a philosopher starves.

I wonder especially about the probability $p_{stop}^{(k,n)}$ that the algorithm will stop, depending on the number $n$ of philosophers that join the diner, $n \leq N$.

$$p_{stop}^{(k,n)} = \frac{|\text{functions $t \in T_k^n$ for which the algorithm stops}|}{|T_k|}$$

with $T_k^n$ the functions $t\in T_k$ with $|\text{dom}(t)| = n$.