Basic setups:

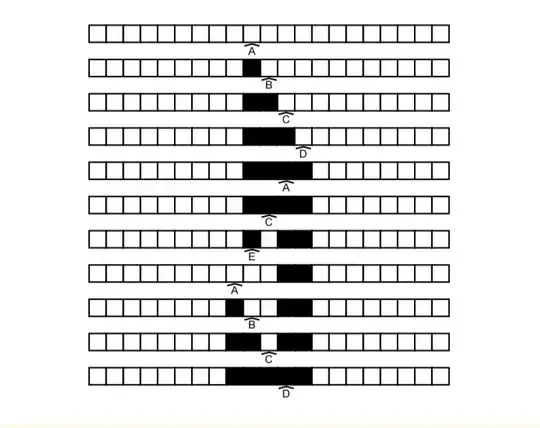

- A Turing machine M operates on a doubly infinite tape. The tape is divided into cells. Each cell can hold either a 0 or a 1 (meaning, we will consider only TM’s with two symbols). The machine has a head, which is positioned on top of one cell. The machine can be in one of a finite number of internal states. The machine also has a transition table, which specifies for each state/symbol combination, what new symbol to write in the cell, whether to move the head left or right, and to which other internal state to go. One of the states is the halting state. If the machine goes into the halting state, it halts. A machine will not necessarily halt, however; it might keep running forever without ever going into the halting state. Initially, the head is positioned on top of cell number 0. Initially, the tape will contain a finite input (located in cells 0 through n for some n ≥ 0) surrounded by all zeros on both sides. Alternatively, the initial contents of the tape might be blank (all zeros). See below Figure1 for an example of a Turing Machine, and the contents of the tape for the first 10 steps, starting from a blank tape. We assume the reader is familiar with the fact that Turing machines can be programmed, i.e.,that one can build Turing machines that process inputs and perform computations on them, just like real-life computers can be programmed (with TM’s having the advantage over real-life computers of having unbounded memory). Therefore, we will not go into the details of how this is done. One can consider several types of scenarios. In one scenario, we run a given TM on an initially blank tape. We consider the question of whether the machine halts, and if so, how many steps it takes to halt.

- The Busy Beaver function: For every $n\in \mathbb{N}$ there exist a finite number of Turing machines with n states. Some of them halt when run on an initially blank tape, and some do not. Let $\text{BB(n)}$ be maximum number of steps an n-state Turing machine runs on an initially blank tape, among all those machines that halt. (The halting state is not counted among the n states.) Hence, BB is a function $\mathbb{N}\to\mathbb{N}$. It is known that BB(1) = 1, BB(2) = 6, BB(3) = 14, BB(4) = 107, and BB(5) = 47176870. The exact value of BB(6) is not known, but below Table1 shows the transition table of a 6-state Turing machine that halts after more than $10 \uparrow\uparrow 15$ steps. (Here $a\uparrow\uparrow b$ denotes $a^{a^{\dots^a}}$,where the exponential tower has height b.) Hence,$\text{BB(6)}\geq10\uparrow\uparrow 15$.

Main question: Suppose I have transition table of a given Turing Machine:

| A | B | C | D | E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1,R,B | 1,R,C | 1,R,D | 1,L,A | halt |

| 1 | 1,L,C | 1,R,B | 0,L,E | 1,L,D | 0,L,A |

Figure1:Transition table of a Turing Machine (top) and the contents of the tape for the first 10 steps, starting from a blank tape (bottom).

Table 1: Best contender machine for BB(6):

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1,R,B | 1,R,C | 1,L,C | 0,L,E | 1,L,F | 0,R,C |

| 1 | 0,L,D | 0,R,F | 1,L,A | halt | 0,R,B | 0,R,E |

My question is that does the Turing machine of Figure1 halt?

My motivation:

The halting state is explicitly defined in the transition table:

- (E,0) → halt: When the machine is in state E and reads a 0, it halts.

- (E,1) → 0,L,A: When in state E and reading a 1, the machine writes 0, moves left, and goes to state A.

From the Busy Beaver function, we know that the best-known 6-state machine runs for at least $10 \uparrow\uparrow 15$ steps before halting. This suggests that verifying halting manually or even computationally is nearly impossible within practical limits.