I tried few cases and found any two spanning tree of a simple graph has some common edges. I mean I couldn't find any counter example so far. But I couldn't prove or disprove this either. How to prove or disprove this conjecture?

7 Answers

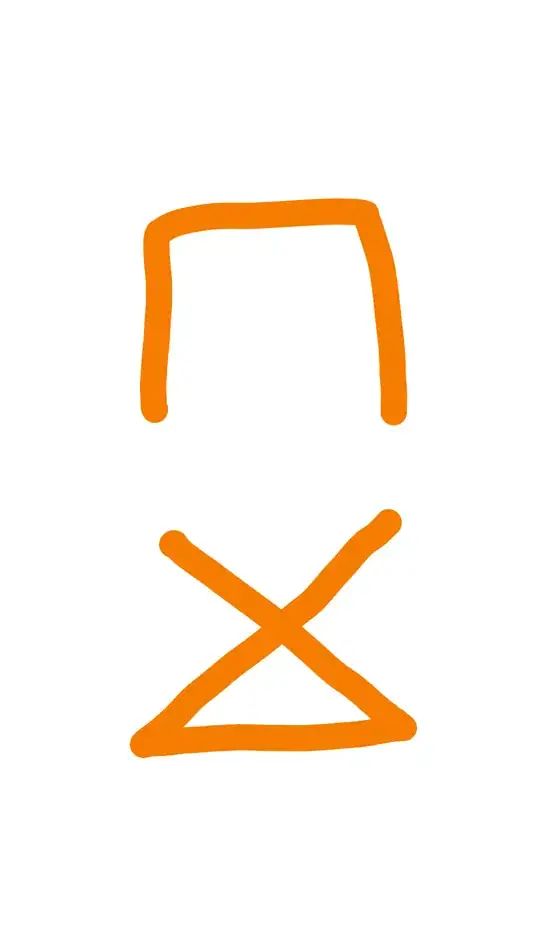

No, consider the complete graph $K_4$:

It has the following edge-disjoint spanning trees:

- 943

- 9

- 19

For the more interested readers, there are some research on decomposition of graph into edge-disjoint spanning trees.

For example, the classical papers On the Problem of Decomposing a Graph into $n$ Connected Factors by W. T. Tutte and Edge-disjoint spanning trees of finite graphs by C. St.J. A. Nash-Williams provides a characterization of graphs that contains $k$ pairwise edge-disjoint spanning trees.

For example, the paper Bi-cyclic decompositions of complete graphs into spanning trees by Dalibor Froncek shows how to decompose complete graphs $K_{4k+2}$ into isomorphic ${2k+1}$ spanning trees.

For example, the paper Factorizations of Complete Graphs into Spanning Trees with All Possible Maximum Degrees by Petr Kovář and Michael Kubesa shows how to factorize $K_{2n}$ to spanning trees with a given maximum degree.

You can search for more. For example, a Google search for decomposition of graph into spanning trees.

- 39,205

- 4

- 34

- 93

EDIT: This is incorrect as pointed out in the comments. As the other answer says, a spanning tree for $K_4$ can be done without sharing edges.

No, it's not true that any two spanning trees of a graph have common edges.

Consider the wheel graph:

You can make a spanning tree with edges "inside" the loop and another one from the outer loop.

- 530

- 1

- 5

- 17

After observing the graphs presented by @Bjorn and @Gokul, I arrive at the conclusion that every complete graph $K_n$ with $n\geq4$ has at least two spanning trees with disjoint edges.

The graph given in the pic, which is wheel, has clearly two spanning trees with disjoint edges. In fact, every wheel will have exactly $2$ spanning trees with disjointed edges because one is complement graph of another.

Now, If we look at the solution of @Bjorn carefully, we find that his graph & spanning trees are homomorphic to the graphs shown in the pic. In fact, every complete graph $K_n$ with $n\geq4$ has wheel as its subgraph, so it directly follows that every complete complete graph with $n\geq4$ has at least 2 (or exactly $2$?) spanning trees with disjoint edges.

P.S: This observation gives birth to $2$ more interesting question.

- Is there any complete graph with more than $2$ spanning trees with disjoint edges? Or it will always have exactly $2$ spanning trees with disjoint edges.

- Is there any graph other than wheel or wheel as its subgraph having spanning trees with disjointed edges?

- 1,301

- 1

- 16

- 38

For $K_{2k}$, I believe that

$$G_1 = \{ (v_{2i},v_{2i+1} ),(v_{2i},v_{2i+2}),\dots,(v_{2k-2},v_{2k-1})\},$$

$$G_2 = \{ (v_{2i+1},v_{2i+2}),(v_{2i},v_{2i}),\dots(v_{2(k-1)},v_{2(k-1)})\}$$

for $0\leq i < k$ are counterexamples. That is, for the first graph, take the vertices with even indices and connect them to the next vertex, and for all but the last even vertex, connect it to the vertex after that as well. For the second graph, do this with odd vertices.

And inductively, once we have a counterexample for $n$ vertices, it's easy to construct a counterexample with $n+1$ vertices by connecting the new vertex with one edge for one graph, and with another edge for the other.

- 82,470

- 26

- 145

- 239

- 710

- 4

- 6

We can show that any complete graph of size $n > 3$ has two edge-disjoint linear trees. Choose $1 < k < n-1$ relatively prime to $n$; this is always possible when $n > 3$. One spanning tree is obtained by the edges $$ E_1 = \{ \{i, i+1\}: 0 \leq i < n-1\} $$ where we identify the vertices with $\{0, \ldots, n-1\}$. For the second tree define $j_0 = 0$ and $$ j_{i+1} \equiv j_i + k\ \mathrm{mod}\ n $$ and set $$ E_2 = \{\{j_i, j_{i+1}\}: 0 \leq i < n-1\}. $$ This defines a spanning tree because $k$ is an additive generator of $\mathbf{Z}/n\mathbf{Z}$.

Suppose $e \in E_1 \cap E_2$ and $e = \{i, i+1\}$. This means that either $$ i+1 \equiv i+k\ \mathrm{mod}\ n \implies k \equiv 1\ \mathrm{mod}\ n $$ or that $$ i \equiv i+1+k\ \mathrm{mod}\ n \implies k \equiv -1\ \mathrm{mod}\ n. $$ The first is impossible because $k > 1$, and the second is impossible because $k < n-1$.

- 141

- 3

If the graph has a bridge (i.e. an edge whose removal disconnects the graph), then this edge must belong to every spanning tree. Intuitively, a bridge is the only edge connecting its two endpoints and so necessarily belongs to every connected subgraph.

On the other hand, if an edge of the graph belongs to a cycle, then there exists a spanning tree not containing this edge.

So, if every edge of a graph belongs to a cycle, then no edge is common to all spanning trees (i.e., the intersection of the edge sets of the spanning trees is the empty set).

- 389

- 1

- 5