I would like to improve the performance of hashing large files, say for example in the tens of gigabytes in size.

Normally, you sequentially hash the bytes of the files using a hash function (say, for example SHA-256, although I will most likely use Skein, so hashing will be slower when compared to the time it takes to read the file from a [fast] SSD). Let's call this Method 1.

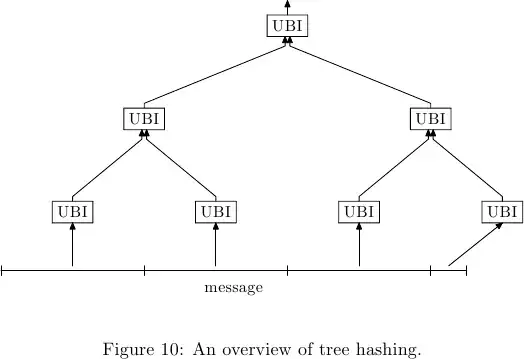

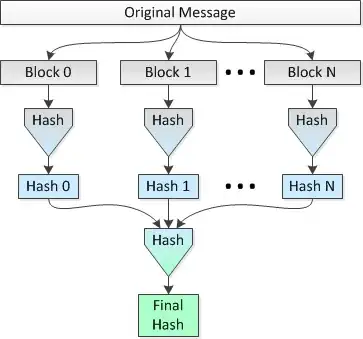

The idea is to hash multiple 1 MB blocks of the file in parallel on 8 CPUs and then hash the concatenated hashes into a single final hash. Let's call this Method 2, show below:

I would like to know if this idea is sound and how much "security" is lost (in terms of collisions being more probable) vs doing a single hash over the span of the entire file.

For example:

Let's use the SHA-256 variant of SHA-2 and set the file size to 2^35=34,359,738,368 bytes. Therefore, using a simple single pass (Method 1), I would get a 256-bit hash for the entire file.

Compare this with:

Using the parallel hashing (i.e., Method 2), I would break the file into 32,768 blocks of 1 MB, hash those blocks using SHA-256 into 32,768 hashes of 256 bits (32 bytes), concatenate the hashes and do a final hash of the resultant concatenated 1,048,576 byte data set to get my final 256-bit hash for the entire file.

Is Method 2 any less secure than Method 1, in terms of collisions being more possible and/or probable? Perhaps I should rephrase this question as: Does Method 2 make it easier for an attacker to create a file that hashes to the same hash value as the original file, except of course for the trivial fact that a brute force attack would be cheaper since the hash can be calculated in parallel on N cpus?

Update: I have just discovered that my construction in Method 2 is very similar to the notion of a hash list. However the Wikipedia article referenced by the link in the preceding sentence does not go into detail about a hash list's superiority or inferiority with regard to the chance of collisions as compared to Method 1, a plain old hashing of the file, when only the top hash of the hash list is used.