- It depends on how long you want to keep your data safe for. Do you

want the secret safe for 1 week, the rest of your life or forever? Will you get in trouble, put in prison or be killed if that secret is revealed to the wrong person?

- It also depends on who you want to keep the data safe from. Do you want your data protected from nation state-level adversaries e.g. US, UK, China, Russia?

- Do you want to consider adversaries that could have viable quantum computers already in secret or very soon in the future <5 years?

Let's assume we want to protect the data from a certain agency with a massive black budget ($10,800,000,000 USD per year) and whose mission is to obtain and decrypt the world's communications. Let's also assume they've got viable quantum computers, we know they have been trying to build one and who at one point was about 20 years ahead of academia in the field of cryptography. If they don't have one just yet, they will do in the next <5 years so you need to consider if you want your data to secret for longer than that.

An important thing to note is that when assessing the security against a brute force search, an attacker does not need to perform the full number of attempts. Let's say you have a 128-bit key, that's $2^{128}$ search operations. That's the worst-case scenario. If they find the right key after $2^{64}$ operations or $2^{72}$ operations then they can stop there, they've cracked your data. There is probably some statistical analysis that could be used to figure out the probability of finding a key faster than brute force search in a certain keyspace. Also, remember that there are attacks against various algorithms that can lower the number of brute force searches required.

You are hoping an 80-bit key will be secure, which is considered by some to be around the current limits of capability when it comes to adversaries with the top regular supercomputers in the world (taking into effect supercomputers with GPUs and CPUs with AES-NI instructions). In a worst-case scenario, this can be cracked in $2^{40}$ time on a quantum computer using the current best quantum search algorithm which is Grover's algorithm. Security of $2^{40}$ is not secure at all.

Given a 128 bit key which is considered by some to be overkill when it comes to adversaries with normal supercomputers, this can be cracked in $2^{64}$ time on a quantum computer which is still not secure at all.

If we move up to a 192-bit key this will take $2^{96}$ time with a quantum computer. Probably the bare minimum security margin nowadays and it might protect your data for a few more years.

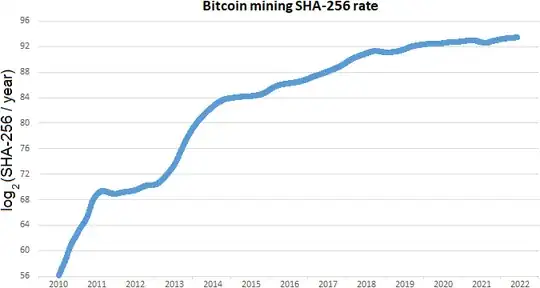

If we move up to a 256-bit key this will take $2^{128}$ time with a quantum computer. If we assume $2^{80}$ is within reach of the top supercomputers in the world and with Moore's law they gain an extra 1 bit of processing power per year, then this will be safe until about the year 2062. You might still be alive by then, and you might still want your secret protected. The established totalitarian government might forcibly remove you from your retirement home and throw you in prison because you sent a mere 256-bit encrypted message to your friend talking about going on an anti-government rally back in 2013. Do you want to risk it?

Your next option is going higher than 256 bits to stop them from cracking your data in your lifetime, then you can rest in peace. With the Threefish algorithm you can have a 512 bit or 1024 bit key. For a 512 bit key that gives at least $2^{256}$ security against a quantum computer. They'll be there until about the year 2190 working away on that one. You better hope they don't capture you, put you in cryosleep then wake you up again when they've decrypted it just to have proof and punish you.

What about if you never, ever want them to find out the real data? What if you're tired of government sock puppets estimating "safe" levels of key bits and "safe" algorithms for you to use? What about if you want the ability to give them any number of fake keys under duress and still have it decrypt to something plausible so you won't get in trouble? Well, then you should use a one-time pad. They can try every key and have it reveal every plausible plaintext but still not know exactly what the real data is. This is the reason spies, militaries and governments use it - plausible deniability. Just don't use a backdoored or potentially dodgy random number generator like Intel's RDRAND. Use proper TRNG.