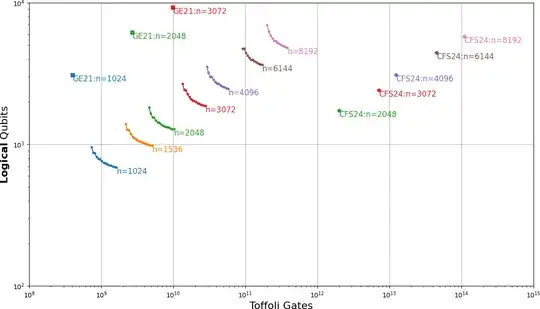

In classical terms, the number of logical qubits roughly equates to the memory requirements of the algorithm. As you note, for Shor's algorithm for factoring, this is roughly linear in $n$. This is due to a a collection of qubits that make up a notional register large enough to hold a small multiple of the period of $a^x\mod N$ as well as another collection of qubits that make up a notional register large enough to hold the value of $a^x\mod n$.

The number of Toffoli gates roughly equates to the number of operations required to perform the algorithm. For example, a naive exponentiation routine $a^x\mod N$ for $n$-bit $a$, $x$, and $N$ would take $O(n)$-multiplications of $n$-bit numbers. If we used the high school multiplication methods this would be $O(n^3)$ bit level operations. As $n$ grows we might hope to see $o(n^3)$ operations as we move away form regimes where naive algorithms are optimal.

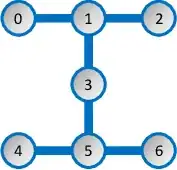

With more gates than qubits, the operations naturally need to be spread out over time. We typically describe quantum circuits using a horizontal line to represent each qubit's evolution over time. Taking a vertical slice through the lines represents the states of the qubits at that point in time. Changes between slices are achieved by gate operations - physical processes that allow us to alter qubit states. The exact physical process varies according to the technology used to build the quantum computer, but as a simple example here is the layout of a 7-qubit IBM super-conducting device

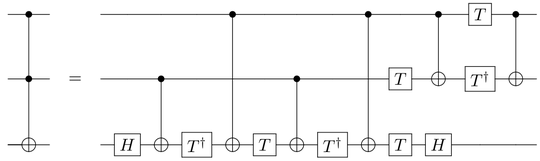

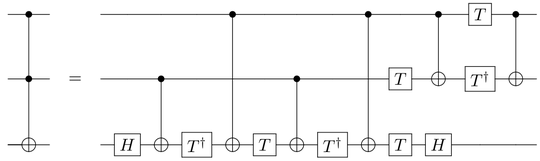

the qubit information can be thought of as living on the numbered nodes. Primitive 1-qubit gates can operate on a single node and primitive 2-qubit gates can operate on the links between them. In both cases this involves applying some physical change at the particular point in time. After the change has been applied the nodes will be in a different state and different gates may be applied. A Toffoli gate is notionally a 3-qubit gate, but can be decomposed into 1-qubit and 2-qubit operations using multiple time slices (12 in the diagram)

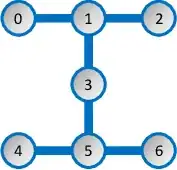

Note that this decomposition is not directly implementable on the IBM layout as it requires 3 pairwise connected qubits. Thus for example, if we wished to implement a Toffoli gate on qubits 0, 2, and 1 in the IBM device we might need the following operations at time slices

- Apply $H$ to qubit 1

- Apply CNOT(2,1)

- Apply $T^\dagger$ to qubit 1

- Apply CNOT(0,1)

- Apply $T$ to qubit 1

- Apply CNOT(2,1)

- Apply $T^\dagger$ to qubit 1

- Apply CNOT(0,1)

- Apply SWAP(1,2)

- Apply $T$ to qubit 1; apply $T$ to qubit 2.

- Apply $H$ to qubit 2; apply CNOT(0,1)

- Apply $T$ to qubit 0; apply $T^\dagger$ to qubit 1

- Apply CNOT(0,1)

- Apply SWAP(1,2)